A century into Charleston’s preservation movement, the conversation has shifted beyond buildings to the less tangible concept of “livability”—which means what, exactly, and to whom?

Editor’s Note: This feature was at the printer before Charleston and its islands and beaches were closed to any nonessential business. Although now, from the very uncertain and sometimes frightening space we find ourselves, this article may come across as outdated—complaints of too many tourists and more hotels being built when the peninsula is a ghost town? We have retained it on the website, as well as in the print edition, as this pause in life as usual might be an apt time to reconsider the future of our city with a bit more perspective.

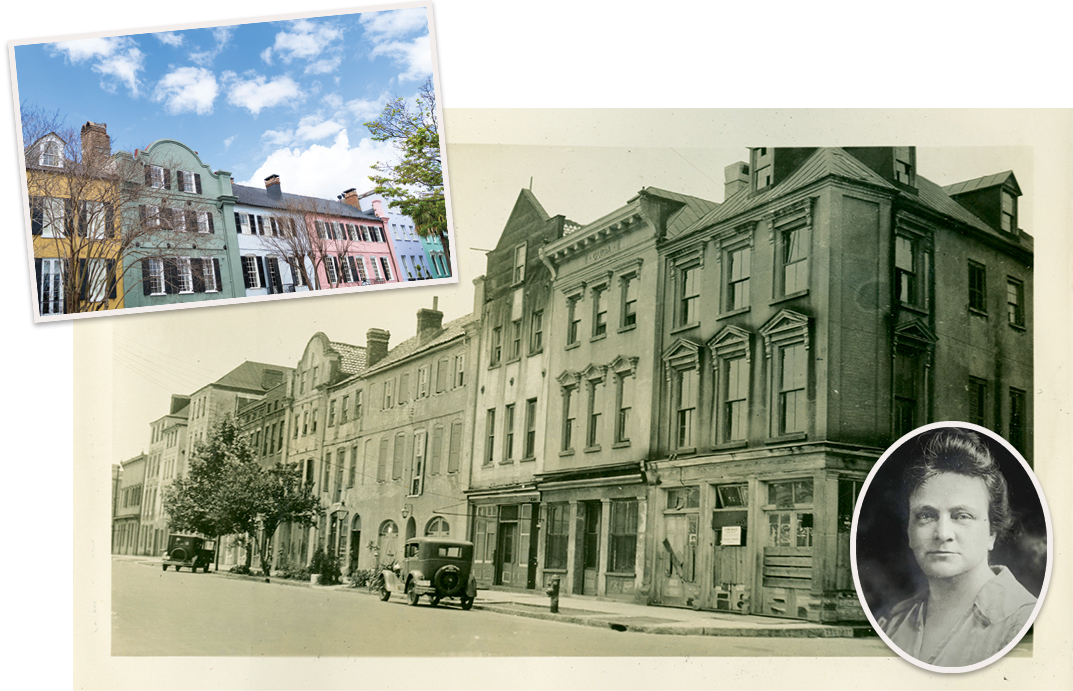

If you’re charmed by Rainbow Row’s cheerful palette or Tradd Street’s intact historic fabric, you have Susan Pringle Frost to thank. When many old buildings were crumbling post World War I, she saw beauty and worth where others saw ruin and decay. Frost became the city’s first female real estate agent in order to buy downtrodden homes then save and restore them. In 1920, she helped found the Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings (now known as the Preservation Society of Charleston), setting in motion a historic preservation ethic that has defined the city ever since.

Fast forward 100 years, and the landscape has changed. This month, as the Preservation Society of Charleston (PSC) celebrates its centennial and Charleston celebrates its 350th, the city’s past, architecturally at least, is well preserved, but her future feels uncertain. Current challenges are less related to building decay than the opposite—rapid growth. While Frost’s cohort may have been “too poor to paint and too proud to whitewash,” an abundance of well-financed developers today are investing in hotels and apartment buildings faster than you can say “B-A-R.”

Judging by last November’s municipal elections, “livability” is the new buzzword, one almost every candidate included in his or her talking points. Indeed a political action committee called the “Lowcountry Livability PAC” is funneling financial support to city and county council candidates who represent their concerns about “livability” issues such as flooding, mobility, tourism management, protecting the greenbelt, and housing affordability. Not only did Mayor John Tecklenburg campaign on livability issues, the city’s website outlines five areas of focus for his second term, including his promise to “preserve and protect the neighborhood livability and resident quality of life that make our city so special.” Likewise the PSC and its partner Historic Charleston Foundation (HCF) are as focused on safeguarding livability as they are on protecting architectural gems.

We talked with leaders in these fields to find out how they understand “livability”—and for whom? In addition to flooding, which all agree is a primary threat, what are the biggest challenges? What are the promising opportunities, and who is doing what to achieve them?

Early preservation advocate Susan Pringle Frost (right) was the first woman in Charleston to earn a real estate license, which she used to buy up derelict properties, including tenements along Rainbow Row (above), and restore them. In 1920, she helped establish the Society for The Preservation of Old Dwellings, now known as the Preservation Society of Charleston.

The Preservation Society of Charleston

To Kristopher King, who has headed the Preservation Society for the last five of its 100 years, the essence of “livability” comes down to the founding principle that Susan Pringle Frost innately understood: “the idea of historic preservation is grounded in the fact that Charleston is not a museum but a living, breathing city of neighborhoods, each with its own character,” King says. Over the years, his membership-based organization has evolved from focusing on the protection of individual properties to protecting the historic fabric of the city. “Yes, architectural details still matter, and we speak up at BAR [Board of Architectural Review] meetings about them, but we also need to manage the macro issues posing an existential threat,” King continues. “Livability means ensuring Charleston remains a place of strong neighborhoods and viable business districts. We work to make sure the patterns of the historic city and the way the city has functioned historically are preserved.”

This is complicated work, with no one-size-fits-all answers, and there is often pushback from residents, including PSC members. For example, King notes, Charleston’s traditional corner stores add a tremendous value and reflect how neighborhoods historically functioned, lending character and enabling residents to walk to shop, thus helping alleviate traffic congestion. But “folks can be resistant to having noise and foot traffic from business use in their neighborhood,” he says. Whether on the peninsula or in the suburban neighborhoods of Mount Pleasant and James Island, he’d like to see a shift from NIMBY-ism to what he calls “YIMBYs—Yes, in my backyard.”

According to King, the biggest livability issues for Preservation Society constituents—those “existential threats”—are over-development, flooding, and over-tourism. As a watchdog membership organization, PSC is focused on educating members about the issues, giving them resources, including an advocacy toolkit with numerous resources accessible on their website, and alerting the public via e-mail in advance of plans going before the zoning board, for example. “We are busy on the ground building community relationships, cultivating networks and neighborhood leadership in the 12 city council districts so we stay ahead of decision making,” King says. “The biggest problem is when people say, ‘How did you let that happen?’ We strive to be proactive, not reactive.”

“The question is how we manage development and tourism going forward....With no vision, there’s no real plan and no accountability, so we’re stuck in a spin cycle.” —Kristopher King, Preservation Society of Charleston

King points to the Sergeant Jasper project on Lockwood Boulevard by Colonial Lake as a turning point for residents and PSC. Both his organization and HCF argued that the 12-story residential and commercial project was too out of scale and “incongruous” for the historic neighborhood. But following years of often-contentious negotiation, the developers prevailed after suing the city. “They exploited a weakness in the wording of the ordinance. It was a game changer,” King says of the development now well underway. The PSC is pushing for stronger ordinances. “The Jasper underscored that we have to get upstream on these projects in order to guide what is an out-of-control market driven by well-funded developers. We were chasing this project from day one.”

King is focused on making sure the city’s revamping of the Comprehensive Plan, due this year, includes plenty of public input. To date, he asserts there has been little communication from the city regarding how and when this will take place. “The question is how we manage development and tourism going forward, by way of strategic vision or letting the free market determine it? With no vision, there’s no real plan and no accountability,” he says, “so we’re stuck in a spin cycle.”

Small, locally owned businesses like Queen Street Grocery, a revived former apothecary and circa-1922 corner grocery in Harleston Village, add neighborhood flavor and create walkable places for food and gatherings. Corner stores were historically a downtown mainstay, notes Kristopher King, “but we occasionally get NIMBY pushback from residents wary of noise and traffic.”

Historic Charleston Foundation

“Livability is a ‘term du jour’—a loaded word that gets bandied about a lot,” says Winslow Hastie, president and CEO of Historic Charleston Foundation. “You have to ask, ‘livability for whom?’”—and because, as he and King both note, the term is often used in the context of the peninsula, “it can get equated with elitism,” Hastie adds. “The word gets used for different agendas and not always for advancing the good of the broader community.”

For Hastie, livability means “making sure that when policy-level decisions are made, all residents’ interests come first,” he says, and points to flood resilience, tourism management, and attainable housing as his organization’s primary areas of focus, often overlapping and in concert with PSC. “We’re looking at issues through the lens of livability,” he says, and for his constituents, flooding tops the list of concerns. “Homeowners for whom we hold historic easements are fed up. The city is overcoming an unfortunate complacency that had crept in following Hurricane Hugo and is now aggressively leading in flood mitigation efforts,” says Hastie, whose organization spearheaded and funded the Dutch Dialogues™ Charleston in partnership with the city to bring national and international water experts to study problem areas for the peninsula, John’s Island, and West Ashley and make a series of recommendations. Hastie and HCF see The Dutch Dialogues™ investment as a way “to keep flooding and resiliency on the front burner,” he says.

“Charleston has experienced massive growth in tourism, and it’s become a war cry for residents.” —Winslow Hastie, Historic Charleston Foundation

Tourism represents “a flood of a different kind,” Hastie says. “Charleston has experienced massive growth in tourism, and it’s become a war cry for residents, with legitimacy,” he says, though he’s quick to add that HCF is “in the tourism industry, so we are looking at how we can be a part of the solution versus contributing to the problem.” Hastie’s predecessor, Kitty Robinson, cochaired the task force that created the city’s 2015 Tourism Management Plan, “and it’s time for that to be revisited, with more teeth and more accountability,” says Hastie, who contends that walking tours are too big and that more data is needed to track tourist behavior and trends. He’d like to see a strategic communications campaign, similar to efforts in Amsterdam, that reminds visitors to be respectful of private property, to convey that, “this is a place where real people live; it’s not an attraction.”

And speaking of a place where real people live, Charleston needs to be just that, affirms Hastie, not just an enclave for the wealthy. “It goes back to the original question, livable for whom?” he says. Until the city solves workforce-housing issues, “those in the service sector can’t afford to live here, which is very much tied to our transportation woes.”

While regulated by the city, horse carriages can add to downtown traffic woes, and tourists crowd sidewalks. The city’s 2015 Tourism Management Plan is in need of updating, with “more teeth and more accountability,” says Historic Charleston Foundation’s Winslow Hastie.

The City of Charleston

“As someone who was born here and has lived here most of my life, I see livability in terms of the big picture, measured by things like job opportunities, inviting public spaces, and cultural opportunities. Frankly, I feel like we’re headed in a good direction,” says Mayor John Tecklenburg. Yes, Charleston is dealing with flooding, with traffic and transportation, and housing costs, he acknowledges, but “most vibrant cities share those kinds of issues. We’re not alone. I’d make a strong case that we’re in a better spot today than we were 10 years ago,” he adds. “As we address our long-term challenges, with flooding and drainage being number one, we remain continually vigilant, looking at everything in terms of livability.”

“As an urbanist, I think of quality of life in terms of choices. Do residents have a choice of where to live, where to send kids to school, how to move around, where to buy groceries? More choices, to me, means a higher quality of life.”—Jacob Lindsey, City of Charleston Planning Department

According to Jacob Lindsey, director of the city’s planning department, improving livability is “our job—our goal is to improve neighborhood livability and quality of life for residents every single day.” As Lindsey and his team go about creating an updated 2020 Comprehensive Plan, he is targeting livability in terms of four issues, the first of which is water. “The former Comprehensive Plan didn’t mention sea level rise and climate change at all,” he says. “Now 10 years later, the tenor has totally changed, and addressing flooding is our first and most important priority.”

Secondly, Lindsey is working to provide more affordable and diverse housing options, including new revenue through development fees on high-density apartments and hotels, which will be used to construct new dwellings within the city. “We’re also working to streamline the approval of affordable housing through the permitting process, and through the Comprehensive Plan, we will work with consultants to adopt the best national policies for protecting existing affordable housing in our neighborhoods.” Another priority is to align growth and transportation, “so development isn’t contributing to traffic congestion but instead helping us create more transportation options,” Lindsey says. And finally, enhancing public safety in the city’s neighborhoods is the fourth focus.

Each of these is a complex challenge, requiring comprehensive data collection and analysis, “which is different than what we’ve done in the past,” explains Lindsey. “In terms of planning, we want to be sure the city is growing in the right places, and not in places that flood or don’t have good transportation connections—places that are high, dry, and connected,” he says, pointing to the West Ashley Master Plan as a good example.

“As an urbanist, I think about quality of life in terms of choices,” he says. “Does a resident have a choice of where to live, where to send kids to school, how to move around, where to buy groceries? More choices to me means a higher quality of life,” he says, and giving people more options is Lindsey’s goal from a planning standpoint.

Lindsey agrees with the mayor that Charleston today is “one of the most livable cities in the country,” he says, but the threats of flooding and sea level rise, housing affordability, and tourism management are real. Other than the hotel ordinance that, he says, has stemmed the loss of important parts of our city to hotels, with the next step to restrain hotel growth, Lindsey notes that the planning office doesn’t do much direct tourism management (the city’s Department of Livability and Tourism enforces ordinance codes, with infractions going before the city’s Livability Court). “If we aren’t vigilant,” Lindsey adds, “any of these three issues could really challenge the city.”

(Clockwise from left) Explore Charleston CEO Helen Hill at the Charleston Visitor Center, which is being redesigned to include interactive elements, such as a demo kitchen, that are inviting for visitors and locals alike, as well as messaging to help “visitors understand that Charleston is a working city,” she says; From a redesigned Visitor Center (scheduled to open late May) to a HOP shuttle to curtail downtown traffic and assist hospitality workers with parking and transportation costs to classes supporting hospitality workers’ career advancement, Explore Charleston is adopting a comprehensive approach to “making sure our entire industry is healthy and whole,” says Helen Hill.

Explore Charleston

“When people say Charleston has too many tourists, we usually agree,” says Helen Hill, CEO of Explore Charleston, formerly the Charleston Convention and Visitors Bureau. It’s to be expected, she adds—“what makes a community a great place to live often makes it a great travel destination.” Recognizing the need to maintain a delicate balance between tourists and residents, Hill has instigated a significant shift in her organization’s mission. “We are a destination marketing and management organization,” she says, clarifying that their focus is not on increasing the volume of tourists but expanding tourism’s economic footprint and developing the industry responsibly. “Our goal is to attract visitors who stay longer, do more, and therefore, spend more,” Hill explains, noting that this trend toward a management focus is unique in the United States, with Charleston being one of the first cities to embrace such an approach.

On the destination marketing side, Hill’s team has worked on expanding air service options in order to attract their target audience, given that visitors originating from New York and Boston, for example, are generally willing to pay higher hotel fees than drive-market tourists. But by road or air, visitors are coming to experience the city’s history, and thus the fact that Charleston was the nation’s first city to adopt zoning for a historic district as well as to adopt a tourism management plan in 1978 is not a coincidence: The two go hand in hand. “History remains a differentiating attribute, the number one reason people choose to visit Charleston,” she says. To keep drawing the type of tourist that Explore Charleston is targeting, the historic fabric and real neighborhood feel of the city need to remain intact, and similarly, the goal is for both the visitor experience and resident quality of life to remain high. “After all, we, too, live here because of Charleston’s unmatched quality of life,” Hill continues.

One way they hope to achieve this is through renovating and redesigning the Visitor Center on Meeting Street. Once re-opened in late May, Explore Charleston will manage the redesigned facility, previously under the city’s purview, and is planning new interactive elements, including a demonstration kitchen to highlight local chefs and foodways, to make the experience inviting for both residents and visitors. “Our goal is to capture visitors before they enter the historic district and help them navigate their visit to minimize impact on residents,” says Doug Warner, Explore Charleston’s Vice President of Media and Innovation Development. “The messaging at the new center will be explicit in helping visitors understand that Charleston is a working city, not Williamsburg. We want visitors and residents to interact because, after all, our people are our most valuable asset,” Hill adds.

“Livability to me means the opportunity to interact with my community and enjoy it. I live and work downtown, so I’m spoiled,” says Hill, who realizes that many hospitality workers are not so lucky, and transportation costs eat into wages for many who cannot afford to live downtown. Explore Charleston, a nonprofit entity, secured private funding to create the HOP (Hospitality on Peninsula) program and worked with the city, the county, and the Berkeley Charleston Dorchester Council of Governments to create a park-and-ride lot and CARTA shuttle service as a case study, the success of which she hopes will be expanded. “We’re now parking 450 cars a day off the peninsula. We proved that park-and-ride will work,” she says. “Residents are happy that streets are less congested and their parking places are protected, and workers have a reliable and affordable means of transportation.”

Hill and her team have also initiated hospitality training programs, offering 32 different classes ranging from customer service to sales to bartending. The goal is to “ensure our entire industry is healthy and whole, and that we create real economic opportunity, including pathways from back-of-house jobs like dishwashers and prep cooks to higher paying front-of-house management positions,” explains Warner. Their workforce programs include outreach like job fairs, as well as recruitment, training, and job placement programs.

Last fall, Explore Charleston also launched a new initiative, Heart for Hospitality, an effort intended to complement existing programs while adjusting the lens through which workforce recruitment, retention, and development are viewed. “Heart for Hospitality is about engagement and inclusion. It’s a commitment to being an industry that more fully represents our community. We’re going beyond basic skills training. That means opening doors of opportunity, identifying mentors, and offering leadership training in areas like unconscious bias,” Hill says. “The great thing about our industry is that it’s a sector where anyone, regardless of background or education, can move up and succeed.”

Coastal Conservation League

Livability, at first glance, may not seem to be a typical priority for conservation groups focused on natural resource and habitat protection. But not so for the Coastal Conservation League (CCL). “It’s very much a part of our DNA,” says executive director Laura Cantral. When the league was founded in 1989, she explains, “the real focus was fighting suburban sprawl, preventing it from eating into our rural landscape and negatively impacting the health of those landscapes, and on the other side of the equation, ensuring we are advocating for responsible and appropriate growth in our communities to improve quality of life for people who live there,” she says.

Over the years, the Coastal Conservation League has been a leader in shaping transportation policy and land-use issues, “making sure the City of Charleston is able to maintain and preserve its unique historical heritage and character,” Cantral says. This is where synergy between conservation and preservation groups comes in. “The natural resources we fight to protect are not just important for the environmental health of our region, they are in fact cultural resources, integral to the history of this place. We see people as part of the ecosystem.” She points to the CCL’s long-standing opposition to the extension of I-526, which would exacerbate sprawl and jeopardize traditional land uses on our fragile sea islands.

“The natural resources we fight to protect are not just important for the environmental health of our region, they are in fact cultural resources, integral to the history of this place.” —Laura Cantral, Coastal Conservation League

The league has different program directors watching over everything from clean water and air to transportation policy and land use. “The health of our natural resources is critical from an environmental perspective as well as for the quality of life benefits they provide—so people can be connected to the land, doing what they love to do, whether that’s hiking and biking or hunting and fishing,” says Cantral.

“Those are important traditional uses that lend to a high quality of life, to improved health, and that’s an important part of our mission.” GrowFood Carolina, for example, an initiative of the CCL, provides access to healthy food and supports local farmers. “This is a tangible way we help people connect to the land and to nature, and improve their health,” she says. “As is advocating for transportation options to allow people to walk and bike more to reduce pollution and give them opportunity and motivation for healthier lifestyles.”

From fighting sprawl to advocating for improved transportation and supporting local agriculture, the Coastal Conservation League counts a healthy quality of life as an integral part of its mission. “We see people as part of the ecosystem,” says executive director Laura Cantral (above left).

Lowcountry Local First

“The first question is what’s your definition of ‘livability.’ It’s very different for one population group than another,” says Jamee Haley, executive director of Lowcountry Local First, a nonprofit that supports local businesses. “If you’re doing well and have a nice home on the peninsula, livability often means not wanting so much new development. But if you’re struggling, then having access to a grocery store, earning a living wage, and finding affordable rent are livability issues.”

According to Haley, the main challenges facing local businesses who make up LLF’s membership are access to affordable commercial space and hiring and retaining qualified employees. “I remind them that it is often an affordable housing issue,” she says. “Is there a place that prospective employees can live close by so they’re not having to spend time and money driving from Summerville? It’s also a wage issue,” she says, pointing to the disparity that the median home sales price increased 27 percent and average rent rose 49 percent from 2010 to 2016, while median household income rose 12 percent (according to the Charleston Metro Chamber of Commerce).

Haley’s team is addressing these issues by educating their members and making sure that elected officials understand the pain points for local businesses, she says. The nonprofit also provides resources and entrepreneurial training to help small businesses get started and succeed.

Another significant way LLF works to preserve and enhance livability is by encouraging more locally owned business, especially those within neighborhoods. “People want to live in a community where they have access to a grocery store, a bank, and a place to get your laundry done—that’s all livability,” Haley says. LLF encourages municipalities to enact “Formula Business District” policies that would prohibit chain-like stores and protect the unique character of a community, as Folly Beach and Sullivan’s Island have done.

“Cannonborough-Elliotborough is ripe for this downtown, but we were told the City of Charleston ‘doesn’t have an appetite for it.’ I feel like they’re so overwhelmed right now they can’t think progressively,” says Haley, who views this as a lack of vision. “The tail is wagging the dog right now. It’s frustrating to me, for example, that the city is spending millions of dollars on creating the International African American Museum, and visitors will walk out of there and not find a local African American business to support. There were legacy businesses nearby that are now gone, and nothing was done, by the city or by the preservation groups, to support them. We need to think about preservation beyond buildings and focus on the people who occupied those buildings and made their living serving the residents of the area.”

“Livability is shaped by what happens in the public realm,” says the director of the Urban Land Institute’s South Carolina chapter, Amy Barrett, shown here at the pedestrian mall on MUSC’s campus, public space reclaimed from a street closed to car traffic.

Urban Land Institute

As a national member organization, the Urban Land Institute provides leadership and fosters conversations regarding responsible use of land, according to Amy Barrett, the director of the South Carolina Chapter. “We represent a lot of private developers who are building things here, so sometimes their interests can be challenging with regards to livability and change. Our goal is to bring together professionals who understand the long-term ramifications and to have better, more informed discussions about land use. To understand all sides so we can make smarter decisions that aren’t emotional and reactionary and won’t come back to haunt us in the end,” says Barrett.

She points to the issue of traffic congestion as one that is particularly fraught. “The go-to answer for many people is to add more lanes. But that’s a short-term fix, and it’s a painful and complicated conversation to explain this to people when they’re feeling the pinch and pain of sitting in traffic. Experts know the right thing to do for the long term is to get people out of cars and give people more alternatives to get around. But that’s a hard conversation to have, and it takes a long time to shift mind-sets.”

“If you’re doing well and have a nice home on the peninsula, livability often means not wanting so much new development. But if you’re struggling, then having access to a grocery store, earning a living wage, and finding affordable rent are livability issues.” —Jamee Haley, Lowcountry Local First

For Barrett, livability means focusing less on physical buildings than “on the life that happens between those buildings. Quality of life means you feel safe, that you in fact have a place to live. Livability is shaped by what happens in the public realm—it’s about how we take care of our parks and our roads—are they safe for bikes and pedestrians, too? To me the mark of an equitable city, a city that prides quality of life for all its residents, is shaped by these public places, by how we provide places for people to gather with those they would not often come into contact with.”

While the last century of historic preservation has set the stage for how we think about our city, it’s time for the conversation to broaden, says Barrett. “Buildings are easier to talk about, they’re physical, whereas land use is abstract, and community benefits and decision-making can be even more abstract. Growth and change is never easy,” she explains. “But the process should be relationship-based, and it’s imperative to understand when those relationships need to expand and include other voices. For the most part, the preservation moment has been largely white and upper class, so it’s an opportunity to add some other voices to the table.”

Photographs by Kevin Ruck; Preservation Society of Charleston; Mike Coker; Kevin Ruck; Alex Duarte; MaryKat Hoeser; Mel Smith Monk; Kate Thorton; & courtesy of Nature Adventure Outfitter.