Journey through time with a photographic tour of Charleston’s centuries-old parish churches and chapels-of-ease

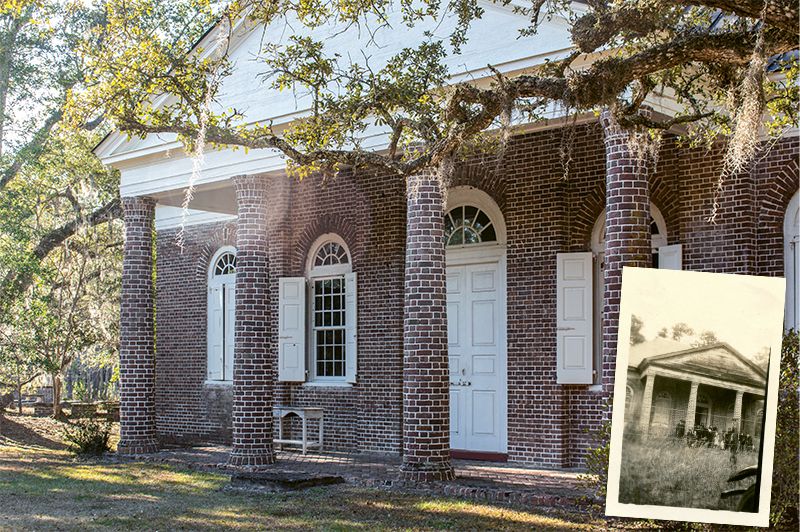

St. James-Santee Episcopal Church at Wambaw today; (inset) in April 1923, Charleston Museum director Laura Bragg arranged a tour of the historic site for participants in the American Association of Museums conference held downtown that year.

Charleston has long been known as the “Holy City” for the graceful steeples that shape its skyline. Yet, beyond the peninsula lies a trove of exquisite parish churches and chapels, some of the oldest extant buildings in the country. Their beginnings date to the Church Act of 1706, which established the Anglican Church of England as the colony’s official religion and created 10 separate parishes, each with its own church and “chapel-of-ease,” a smaller, satellite house of worship erected to serve congregants living in more remote areas.

Despite three centuries and the ravages of war and nature, an astounding number of these houses of worship have survived. Some only hold services once or twice a year, others continue with dynamic congregations and regular Sunday services. All represent a wealth of architectural, cultural, and historical importance. Journey with us—from Old Brick Church in McClellanville, to the treasured chapels along the Cooper River, to the burned-out ruins of Pon Pon and Biggin—and explore these fascinating portals to the past.

Editor’s Note: Protecting local historic churches and chapels-of-ease is paramount. Due to vandalism and their physical remoteness, most are gated, locked, and fitted with cameras. The monies for this security, as well as for maintenance and preservation, comes mostly from private sources. Tours are occasionally offered through various preservation organizations, and many of the churches welcome visitors during services. “While most of the people who come to the annual services at Brick Church and other chapels are friends and affiliated in some way, we enjoy having guests,” says church custodian and historian Seldon “Bud” Hill of the former St. James-Santee parish church in McClellanville. “Just bring a casserole for the picnic afterwards—with your checkbook on top.”

St. James-Santee (Brick Church at Wambaw),

McClellanville

Structure: Circa 1768

Status: Inactive, except for an annual service; Episcopal, Diocese of South Carolina under the aegis of St. James-Santee Episcopal Church

Location: Old King’s Highway, McClellanville

Contact: (843) 887-4386, stjamessantee.org, stjamesec.org/brickchurch.html

Driving the Old King’s Highway is best done unhurriedly, at the slow and steady horse-hoofed clip-clop of its 17th-century origins. The forgotten dirt byway today is pocked with ruts and dips and bordered by endless green woods. There’s not a telephone pole for miles—not one trace of the modern world in view. Every rotation of the car wheels takes travelers back in time.

Ahead in a clearing, standing in muted elegance is the old Brick Church, the parish center for St. James-Santee. Its tall, brick-pillared portico and white Palladian doors invite the same formal welcome to prayer as when the church was built 250 years ago, only those who knelt in its pews in 1768 now rest peacefully in the churchyard outside.

Sometime prior to 1714, a wooden structure was built near Echaw Creek to serve the parish; it was the first of three churches on the site. In 1768, the present Georgian brick building was erected near Wambaw Creek, hence the name, “Brick Church at Wambaw.”

Like other parish churches, Brick Church suffered after the Civil War when most of the congregation moved from their Santee River plantations. By 1918, only an annual service was being held, and the chapel-of-ease in McClellanville (pictured below) became the parish church.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Old St. Andrew’s Parish Church,

West Ashley

Structure: Built circa 1706, enlarged 1723

Status: Active, Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina

Location: 2604 Ashley River Rd., West Ashley

Contact: (843) 766-1541, oldstandrews.org

On busy Ashley River Road lies the oldest extant church building south of Virginia. “It shares the birth year of one of our oldest founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, and predates iconic Old North Church in Boston and Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg,” notes parish historian Paul Porwall.

The first church, a small rectangular wooden structure, was enlarged in 1723, creating the present cruciform, or cross-shaped, floor plan. A main entrance, called the “great door,” faced the river and welcomed the gentry; the “small door” on the west side was used by commoners, servants, slaves, and clergy.

The first minister, Reverend Francis LeJau (d. 1717), is buried beneath the altar. Along with the wealthy white congregation, LeJau also ministered to African slaves and the Native Americans in the parish. He encouraged the establishment of a school and, in 1712, the first schoolmaster, Benjamin Dennis, noted that he had 29 students, six of whom he taught at no charge: “two blacks, two Indians, and two whites.”

While the British occupied the church and grounds during the American Revolution, only the parsonage was burned. Similarly, although Union troops set fire to every plantation along the Ashley River save Drayton Hall, the sanctuary was remarkably untouched by the Civil War.

In its heyday, Old St. Andrews served the wealthy owners of prominent Ashley River country seats like Ashley Hall, Drayton Hall, Middleton Place, and Magnolia Plantation. There were also less prosperous parishioners, as remembered by Reverend John Grimke Drayton in 1876 during the first service held after the Civil War: “Various trades found occupation here, from the English gardener who adorned the pleasure grounds of the wealthy, to the poor man, of whom we read in the old moth-eaten register, who supported himself by mending broken china.”

Adds Porwoll, “Reverend Drayton was the most influential person in the long history of Old St. Andrew’s.” After the Civil War, he sought to improve the lives of people of color through his ministry, just as much as his famous aunts Sarah and Angelina Grimke did with their abolitionist writings and speeches. “That freedmen in St. Andrew’s Parish sought out Reverend Drayton and asked him to restart worship services speaks volumes about their mutual relationship.”

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

St. James’ Parish Church, Goose Creek

Structure: Original wooden church, circa 1708; present edifice, circa 1719

Status: Inactive; privately owned and open only for annual services

Location: 100 Vestry Ln., Goose Creek (gated, locked, and surveilled by cameras to protect against vandalism)

Contacts: Bradish J. Waring, Senior Warden, bwaring@nexsenpruet.com

This second oldest church building in South Carolina originally served the wealthy Barbadian planters (“Goose Creek Men”) and their families. Perhaps the most elaborately adorned of all the parish churches, the Georgian brick edifice, covered in stucco, is graced by tall, arched windows and a distinctive jerkinhead, or half-hipped roof.

Of particular merit is the carved plasterwork above the main entrance doors. The entablature holds a row of five carved flaming hearts, recalling the passage in Luke 24:32, “Did not our hearts burn,” when the disciples met Christ on the road to Emmaus. Above, in the triangular pediment, the “pelican in piety” evokes the legend of the pelican who pierces her breast to feed her young with her own blood, thus symbolizing Christ’s sacrifice upon the cross. Over each of the arched windows are carvings of winged cherub heads.

Among the interior wall ornamentations and framed by tall, Corinthian pilasters are the coat of arms of King George I, which, according to tradition, kept the British from burning the church during the Revolutionary War.

“Back in the late 1980s, the church was in very poor shape,” says senior warden Bradish J. Waring. After a full restoration, the church remains in excellent condition thanks to ongoing maintenance. “We are scrupulous about this, but it is expensive,” notes Waring. “Donations are gratefully accepted—and always much needed. We welcome all who are interested in the church, its history, and architecture and wish to participate.”

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Strawberry Chapel-of-Ease, Berkeley County

Structure: Circa 1725

Status: Inactive; privately owned, four services are held annually

Location: West Branch of the Cooper River, near Cordesville; (gated, locked, and surveilled by cameras to protect against vandalism)

Contact: Robert Ball at jmcdb49@yahoo.com

Strawberry Chapel is the only remaining trace of Childsbury Town, a thriving community established in 1706 by colonist James Child adjoining his Strawberry Plantation, hence the chapel’s name.

In the early 1700s, Childsbury was the “frontier,” a major Native American trading post with a busy ferry that crossed the Cooper River to Goose Creek. The town ultimately became an important market center, with homes, shops, a school, and the requisite tavern. For reasons still uncertain, the town ceased to exist before the turn of the 19th century.

Similar in plan to St. James’ Goose Creek, with a jerkinhead roof and stuccoed exterior, Strawberry was originally established as the chapel-of-ease for St. John’s Berkeley Parish, also known as Biggin Church (opposite), to serve the rice planters along the Cooper River’s West Branch.

With understated architectural elegance, doors open on the north, south, and west sides; bull’s-eye windows ornament both gable ends. While the building is now stuccoed, the under bricks are laid in Flemish bond with tooled mortar joints, suggesting that the brickwork was originally exposed.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

The property near Moncks Corner was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977: “Notable architectural details which remain include a Gibbs surround at the main portal, quoins at the corner, radiating voussoirs over the windows, and a rounded water table.”

Biggin Church St. John’s, Berkeley County

Structure: Original, circa 1712

Location: Hwy. 402 between Cordesville and Moncks Corner

The parish church for St. John’s, Berkeley, was built in 1712 on three acres donated by Landgrave John Colleton at the head of Cooper River between Wadboo and Biggin creeks, hence the name, Biggin Church. Fire destroyed the first wooden structure in 1755. Rebuilt in 1763 in brick, the building was used by the British as a depot for supplies during the American Revolution, after which they set it afire. Rebuilt again, the church fell into ruins after the Civil War. By 1899, the northern and eastern walls had crumbled, and Strawberry Chapel became the parish church.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

The church was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

St. Thomas Parish Church, Berkeley County

Structure: Early wooden structure, circa 1708; present edifice, circa 1819

Status: Inactive; Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina. The property, now a mission church of The Church of the Holy Cross on Sullivan’s Island, is open only on special occasions.

Location: 1507 Cainhoy Rd., Wando

Contact: (843) 883-3586, holycross.net

Also known as “the White Church,” St. Thomas was erected in 1819, replacing the 1708 wooden building which burned in a forest fire. The National Register of Historic Places describes it as “charming in its simplicity of design,” a “uniquely beautiful example of the small, rural parish church of the early 1800s, built with Classical Revival or late Federal features, made of stucco over brick.”

Buried in the churchyard is wealthy colonist Richard Beresford who, after his accidental death in 1721 “from a falling tree limb,” left one-third of his sizeable estate for the establishment of a free school in St. Thomas Parish. The trust, called the “Beresford Bounty,” has remained active for almost 300 years, the funds now earmarked for the upkeep of the church and grounds. Since 1957, St. Thomas has been a mission church under the auspices of the Church of the Holy Cross on Sullivan’s Island.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Pompion Hill Chapel-of-Ease,

St. Thomas Parish, Berkeley County

Structure: Original, circa 1703; present edifice, circa 1765

Status: Inactive, privately owned

Location: On the Cooper River near Huger; (gated, locked, and surveilled by cameras to protect against vandalism)

Contact: Richard Coen, Pompion Hill Chapel Foundation, Inc., 109½ Church St., Charleston

The National Register of Historic Places refers to this chapel as “a miniature Georgian masterpiece, original and unaltered.” Completed in 1765, it replaced a circa-1703 cypress building. The unusual name comes from nearby Pompion Hill Plantation, colloquially pronounced “punkin.”

“Of the Anglican chapels-of-ease, Pompion Hill epitomizes the architectural link with early English ecclesiastic buildings,” says chapel board member Liz Tucker. “All through England, and Barbados, are chapels that look just like ours.”

The layout follows the typical colonial rectangular plan, topped with a jerkinhead slate roof. The interior, however, differs in that the pulpit is at the western, or vestry end, and the communion chancel is at the eastern end and backed by a tall Palladian window. Between, are pews arranged facing each other across a center aisle. Pews on the west side were painted white, supposedly to designate where the white parishioners sat; those on the east painted brown to indicate the seats of the slaves. The floor tiles were given by wealthy merchant Gabriel Manigault who, at the time, owned nearby Silk Hope Plantation.

Construction is attributed to Charleston master cabinetmaker William Axson, Jr. and brickmaker Zachariah Villepontoux. Both have their initials carved on the structure. The interior woodwork and furnishings are all original.

Recent renovations have remedied foundation issues caused by unsettled ground, moisture, and stress on the masonry walls from the slate, which was placed on the roof in 1840. More than $500,000 was raised through the chapel’s foundation to meticulously restore the building to its original condition, with experts performing paint analyses to ensure that the woodwork matched the original 18th-century colors.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Christ Church near Snee Farm was established as the main house of worship for the parish East of the Cooper River.

Christ Church Parish, Mount Pleasant

Structure: Original, circa 1708; rebuilt circa 1725; present edifice, circa 1788

Status: Active, Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina

Address: 2304 Hwy. 17 North, Mount Pleasant

Contact: (843) 884-9090, christch.org

When Christ Church Parish was established in 1706, there was no town of Mount Pleasant. Only farms and plantations dotted the lands on the east side of the Cooper River, then known as “Wando Neck.” Boats provided transportation along the Wando River and up Shem Creek. There was only one main “road,” the Old King’s Highway (later known as the “Georgetown Stage Route”), upon which today’s Highway 17 North was laid out.

Two years later, the first church, a small timber structure, was built by vestryman and carpenter David Maybank of Hobcaw Plantation (today’s I’On). An accidental fire destroyed this building in 1725, and a brick church replaced it shortly thereafter.

This edifice lasted until 1782, when British troops marching north after losing possession of Charleston purposely torched the sanctuary, burning it to the ground. In 1788, the present church was built on its foundation.

By this time, more than 100 families resided or had plantations in the parish, many of whom would become historically important. Two signers of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Lynch, Jr. and Edward Rutledge, are among the many notables buried in the churchyard, as is Charles Pinckney of nearby Snee Farm, a signer of the Constitution.

The church again suffered during the Civil War when Federal troops using the sanctuary as a stable for their horses burned most of the interior for firewood, including the pulpit, doors, windows, and pews. It wasn’t until 1874 that the church was restored.

“Architecturally, Christ Church is representative of the continuous ingenuity displayed by a rural community in keeping its religious center operative,” notes the nomination for the church’s placement on the National Register of Historic Places. “The original early colonial architecture has been adapted several times as the result of numerous events in the church’s long history… but essentially its colonial architectural integrity has been maintained.”

Christ Church remains an active, growing Episcopal church. In 1996, a larger sanctuary was erected behind the historic church, which is now used for special services and early communion on Sunday and Wednesday mornings.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

St. Andrew’s in the Old Village served as the chapel-of-ease for congregants who lived or summered near the harbor.

St. Andrew’s Church, Old Village, Mount Pleasant

Structure: Original, circa 1835; present Gothic Revival building, circa 1857

Status: Active, Anglican Church of North America, Diocese of the Carolinas

Location: 440 Whilden St., Mount Pleasant

Contact: (843) 284-4310, standrews.church

Located in the heart of Mount Pleasant’s Old Village, St. Andrew’s originated as a chapel-of-ease for Christ Church to serve Wando Neck planters who had summer cottages on the harbor. The first chapel was built in 1835; it was replaced in 1857 by the present Gothic Revival edifice designed by Edward Brickell White (also architect of Charleston’s French Huguenot Church). St. Andrew’s became its own parish in 1954 and remains an active church, now affiliated with the Anglican Church. Last year, when a fire burned the adjoining Ministry Center to the ground, the historic church suffered no damage.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Crumbling walls, part of a cistern, and a churchyard are all that remain of this chapel-of-ease off Parkers Ferry Road, formerly a busy stagecoach road between Charleston and Savannah.

Pon Pon Chapel-of-Ease (Burnt Church), Colleton County

Structure: Brick façade, circa 1819-1822

Status: Inactive

Location: Parker’s Ferry Road, off Hwy. 64 between Jacksonboro and Walterboro

Contact: Colleton County Historical and Preservation Society, 205 Church St., Walterboro; (843) 549-9633; cchaps.com

When this brick chapel-of-ease in St. Bartholomew’s Parish (now Colleton County) burned circa 1801, it became colloquially known as “Burnt Church.” Rebuilt between 1819 and 1822, the structure’s central entrance was flanked by windows designed with semicircular arches; the brick walls were laid in Flemish bond. Use of the chapel continued until 1832, when it was again reduced to ruins. Hurricane Gracie toppled much of the remaining structure in 1959; recent hurricanes have destabilized much of what’s left. It is now owned and protected under the auspices of the Colleton County Historical and Preservation Society.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Trinity Episcopal Church, Edisto Island

Structure: Original circa 1774; second, circa 1840; and present building, circa 1876-1880

Status: Active; Anglican Church in North America, Diocese of the Carolinas

Location: 1589 Hwy. 174, Edisto Island

Contact: (843) 869-3568, trinityedisto.com

Trinity Episcopal was established in 1774 as a chapel-of-ease for St. Paul’s Parish to serve Edisto Island cotton planters. The current one-story wooden meeting house—the only example of Victorian church architecture on Edisto Island—dates to 1880. It replaced an earlier church, built in the 1840s, which was destroyed by fire in 1876. Trinity Episcopal remains an active church, now affiliated with the Anglican Church.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Grace Chapel (The Church of the Holy Cross),

Sullivan’s Island

Structure: Original, 1813; present Gothic Revival structure, circa 1907

Status: Active; Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina

Location: 2520 Middle St., Sullivan’s Island

Contact: (843) 883-3586, holycross.net

Sullivan’s Island’s first Episcopal church, Grace Chapel, was erected in 1813 for families who spent the summers on the barrier island. Its original location, almost directly behind Fort Moultrie, caused it to endure severe damage by shelling during the Civil War, and by 1879, the church was declared inactive.

In 1905, a new building was erected one block east of Fort Moultrie and given the name Church of the Holy Cross. Two years later, expansions at Fort Moultrie required the congregation’s removal to a new site. An identical edifice was built near Station 24, the Church of the Holy Cross that continues to serve the island today. The original church building served as the post chapel until Fort Moultrie was decommissioned in 1947. It is now a private residence.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Grace Episcopal Chapel, Rockville

Structure: Original, circa 1840; present building dates to the 1880s

Status: Active, Sunday services from June to August; affiliated with the Anglican Diocese of S.C. under the aegis of St. John’s Parish Church

Location: Grace Chapel Rd., Wadmalaw Island

Contact: (843) 559-9560, stjohnsparishchurch.com/grace-chapel

Originally called the “Church on the Rock,” Grace served the Wadmalaw Island planter families who summered in the village of Rockville on Bohicket Creek. The building was spared during the Civil War; however the parish’s main church, St. John’s, was destroyed by fire, as was a similar chapel-of-ease at the summer community of Legareville on John’s Island. The church was moved to its present location in 1884; the chancel (the area around the altar reserved for the clergy and choir) was added in 1890. Following the great hurricane of 1893, the chapel was used by the American Red Cross and founder Clara Barton, as a center for recovery efforts. The chapel operates under the aegis of St. John’s Parish Church and holds regular Sunday services during the summer months.

For more information and images, visit the SC Picture Project.

Photograph courtesy of The Charleston Museum; Image (watercolor) courtesy of Gibbes Museum of Art; Photograph (interior) courtesy of South Carolina Historical Society