How bird pepper sauce spiced up Charleston in the 19th century

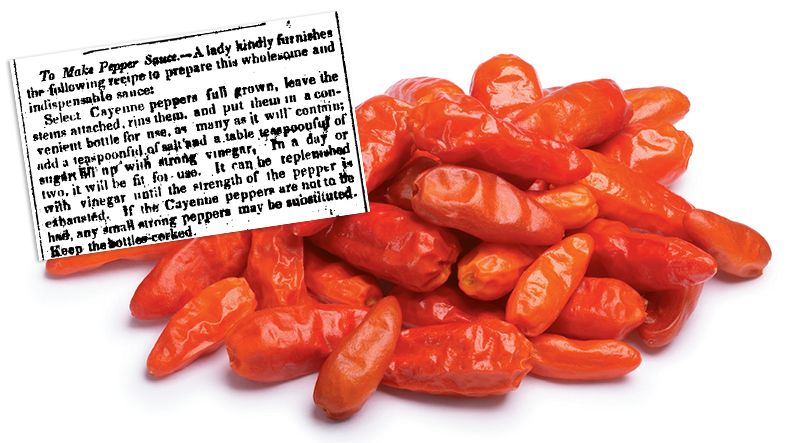

The bird pepper, a chili smaller and hotter than the cayenne, was used in the South to make hot sauce throughout the 18th century; recipes for the condiment were often published in newspapers, like the Southern Sentinal (inset).

Tabasco and the Holy City’s own Red Clay may be household hot sauce staples today, but nearly two centuries ago, Charlestonians enjoyed a different kind of heat: Jamaican bird pepper sauce. Piquant, potent, and popular, the bird pepper (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum) is a small, red chili, cousin to the cayenne and native to the West Indies, northern South America, and southern North America.

Many incorrectly associated the bird pepper with Africa when, in fact, black West Indians had introduced it to the Americas. Their style of vinegar-based, bird pepper hot sauce is a bright concoction of roasted, ripe bird peppers—pureed, salted, soaked in sherry vinegar, and aged in a cask.

Throughout the 19th century, bird pepper sauce, and the chili itself (both fresh and dried), were wildly popular imports. One could buy the dessicated powder for pennies a sack in markets throughout the South. City pharmacies often purveyed the peppers as herbal remedies for various ailments. In an 1850 advertisement printed in the Concordia Intelligencer, a New Orleans druggist offered bird peppers in his catalogue of “Pure Fresh Medicines” alongside other botanical wonders such as milkweed and foxglove. People also bought the peppers and saved the seeds to plant at home. And soon enough, the bird pepper began appearing regularly in many a Southern garden.

Rather ornamental, the bird pepper plant grows small, flame-like chilies that jut skyward, like candles. Once harvested, families could prepare their own hot sauce at home, aided by recipes printed in local newspapers. In New Orleans, some families sold their homemade bird pepper sauce (known there as “sauce piment,” or “ZoZo sauce”) in local markets through the late antebellum period. Few, however, produced on a commercial scale.

But in Charleston, sometime between 1850 and 1851, Alexander Noisette began selling Bottled Cayenne, for 25 cents a pop. Born in 1808, Alexander was the eldest son of Phillipe Noisette, a French horticulturist. Alexander’s mother, Celestine Noisette, had settled stateside after the Haitian Revolution. Alexander, his mother, and his siblings had all been listed as slaves on the census rolls, but were freed by special act of the legislature shortly before Phillipe’s death in 1825.

Alexander continued his father’s horticultural pursuits and ran the most famous vegetable farm in South Carolina—one that operated well into the 20th-century under the direction of Alexander’s sons and was frequently extolled in the national press for its scientific agriculture; breadth of coverage; and quality of produce, all grown and processed on his farm on the Charleston Neck. The recipe for the Noisette family’s bird pepper sauce is now unknown, but it is likely a Caribbean-style blend, perhaps provided by Celestine from her native Haiti.