Pouring over the history of the Charleston Teapot, one of the city’s first gourmet groceries

PHOTO: A forerunner to modern-day artisan grocery stores, the Charleston Teapot (pictured with its iconic teapot sign on King Street, circa 1905) supplied high-end teas, coffees, sweets, and more.

Though circa-1800 Charleston had long harbored a taste for tea—adding it to many society punches, welcoming experimental tea plantations, and making it women’s preferred afternoon stimulant—the Charleston Teapot, opened on King Street in 1873 by Samuel H. Wilson, was the first commercial emporium for the caffeinated beverage in the city.

Selling high-grade black and green teas selected by William Ah Sang and imported from China, the store quickly became sought out for its quality, novel products. As one advertisement noted, “The rich man’s necessity, the poor man’s luxury, everybody’s friend, the greatest blessing vouchsafed to man, which is to be found in its pristine purity, fresh from the dewy fields of the Flowery King, at the Charleston Teapot!”

Wilson soon discovered, however, that man’s “greatest blessing” was insufficient to prop a growing business. In April 1874, he expanded his stock to include sugar in various grades and Javanese coffee. He then erected a coffee roasting machine on the premises and ground beans daily, making the shop smell fresh and fragrant.

Once Wilson grasped that diversifying the scents and tastes he offered was the key to success, he began seeking products rare to the city. Smoked tongue appeared in the store in July 1874, followed by fine canned salmon from the Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River that August. Smoked and prepared fish became one of the shop’s specialties, along with a wide range of cookies and crackers. In autumn 1878, the following types of crackers were advertised: milk, soda, butter, coconut, chocolate, zoological (i.e. animal crackers), oatmeal, Champagne, egg, fruit, and a hard “Boston” variety.

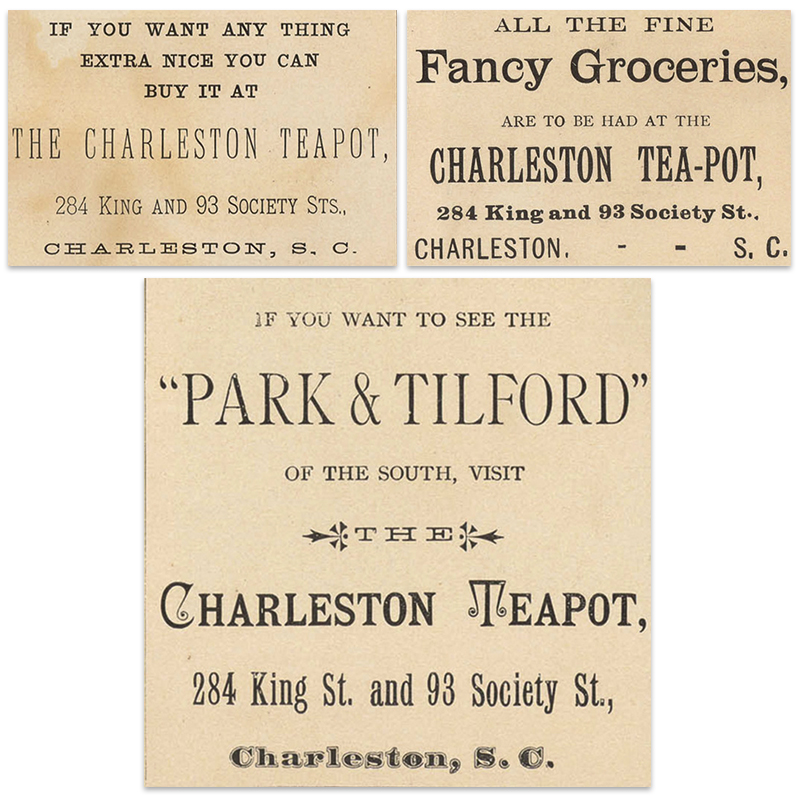

PHOTO: These advertisements circulated in an 1886 pamphlet called The Charleston Earthquake.

By the early 1880s, Wilson was determined to make it a high-end grocery, selling dried fruits, marmalades and jams, table wine, liquor, spices, and canned goods. To the entire custom, Wilson granted free samples of his products. His success was so great that by 1887, he presided over “The Largest Family Grocery in the South,” as the papers proclaimed.

After succeeding in the grocery business, the entrepreneurial Wilson was ready for his next challenge, and so he and a partner opened the Dime Savings Bank for small accounts. Wilson eventually turned management of the grocery over to his partner, Henry R. Lucas, though he kept a guiding hand over it. But when disease struck Wilson in 1909, he was prompted to resign the business, and he died soon after.

Unfortunately, Lucas did not have the acumen of his mentor, and by late spring of 1914, the credit situation of the Teapot—the flagship emporium of its sort in Charleston—was so perilous that the bankruptcy court intervened. The business was sold at auction shortly thereafter. Sadly, the famous teapot sign that graced King Street for so many years (pictured above) was burned in a fire during the winter of 1915.

Images (King Street & Advertisements-3) courtesy of Historic Charleston Foundation