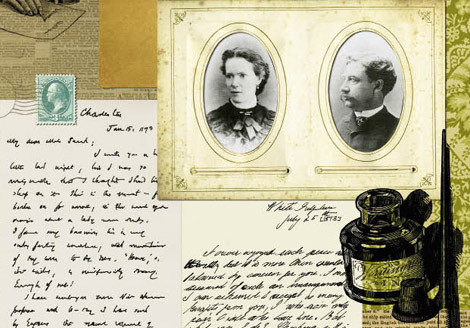

Francis & Sarah Dawson {1873-1889}

The romance between Francis Warrington Dawson and Sarah Morgan was an affair of the heart and the mind. It took place after the Civil War, but that epic period was, in some ways, the reason the two met and she was propelled into the unlikely profession of journalism.

Francis, known as Frank to his friends and colleagues, was the handsome 32-year-old editor of the Charleston News. An Englishman by birth, he had immigrated to the States to fight for the Confederacy and, after the war, became a reporter for newspapers in Richmond, Virginia. There, he met fellow journalist and mentor Bartholomew Riordan, whom he followed to the Holy City in 1866 to a post at the Charleston Mercury and a plan to start their own paper. A year later, Frank married Virginia Fourgeau, and he and Riordan, with financial backing from New York, purchased the Charleston News. In January 1873, bereft after his wife’s death from tuberculosis, Frank left for Columbia, South Carolina, to visit James Morgan, a friend from the war.

Sarah, a former New Orleans debutante, was living at her brother’s home near Columbia, having been forced to leave her native Louisiana with her mother and young nephew. She, too, was in mourning, as the Morgans had suffered much during the war. One brother had fallen victim to a duel; two others were killed while fighting for the Confederacy. Her father then died from a severe asthma attack. In New Orleans, Sarah consoled herself in part through writing, and her journal provides a fascinating chronicle of a life under siege. When the family’s house was burned to the ground by marauders, she confided to her diary, “O my home, my home! I could learn to be a woman there, and a true one, too. But who will teach me now?” After moving to South Carolina, the 30-year-old was determined to overcome her fears and embrace self-reliance, vowing to die rather than be dependent on someone else.

In January 1873, Frank met Sarah at the home of her brother, James, and was immediately taken by his “Guardian Angel.” When Frank returned to Charleston, he wrote her constantly. “You are the complement of my life,” he said, “its crown & completeness & so, time shall show.” Sarah, strong-willed and opinionated, doubted the constancy of Frank’s love. So he tried a different approach: he offered her a job writing for the paper, thus she could secure her independence and help support her family. Sarah accepted his offer with one stipulation: that there be no socializing between them. “I alone shall make my own conditions,” she told him.

Her success was meteoric, and under Frank’s tutelage Sarah brightened and soared. Her first editorial, about the conditions in Louisiana during Reconstruction, appeared on March 5, 1873. That year, she wrote more than 70 pieces on topics ranging from French and Spanish politics, race relations, and women’s property rights to funerals and fashion gossip. Of course, as a woman, she had to write under a male pseudonym (“Mr. Fowler”), but Frank gave her free rein to explore any issue she wished. The following year, he asked her again for her hand in marriage. This time, she accepted.

The couple had three children, and in addition to Sarah’s duties as a wife and mother, she wrote book

reviews for the newspaper. Sadly, their partnership ended during a bizarre incident in 1889, when Frank was killed defending the honor of the family’s governess against the improper advances of a neighbor, Dr. Thomas McDow. Once again finding solace in her writing, Sarah continued to pen articles for newspapers and magazines as well as book translations from Charleston and then Paris, where she died in 1909. Although Sarah’s later writing may not have found as prominent a platform, the Dawsons’ union of heart and mind not only liberated her from the domestic sphere to which Southern society would otherwise have consigned her but also gave women a voice.

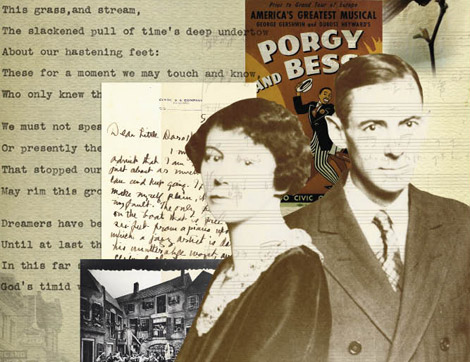

DuBose & Dorothy Heyward {1922-1940}

The courtship of DuBose Heyward and Dorothy Kuhns could have been scripted for a Broadway play. Two aspiring writers—he from a Southern patrician family, she from the conservative Midwest—meet at an artists’ retreat, fall in love, inspire each other from afar, and eventually help create the great American opera, Porgy and Bess, a transcendent story of human passions and human rights.

DuBose Heyward, a blue-blooded Charlestonian whose family—like most—had lost everything in the Civil War, was a reluctant insurance salesman who longed to become a writer. In 1922, he won a coveted fellowship at the MacDowell Colony for writers, poets, playwrights, artists, and composers in rural New Hampshire. Dorothy Kuhns, of Ohio, likewise had been expected to live her life in an “acceptable” way. Instead she took off for New York to learn show business. After a brief stint as a chorus girl, she enrolled in a playwrighting workshop at Radcliffe College and also ended up at MacDowell that summer.

When Dorothy first fell for the “slender, dreamy young man” who laid his hand on hers and locked her gaze, she was convinced that more lay in store for him than a mundane life of sales calls and social engagements. At MacDowell, they were only apart when writing, and at night they roamed the woods and talked of their artistic dreams. They even snuck away one weekend to New York, staying in the same railroad car even though they weren’t married—quite a daring adventure in 1920s America.

That fall, DuBose returned to Charleston and pined for Dorothy for the next nine months. To temper his heartache, he barraged her with long-distance love letters. DuBose hated the monotony of the office, describing himself as “lost among human business machines.” He dreamed of a life sustained by art and love alone and asked her if she would be willing to marry him: “It would be a big risk,” he wrote. “We’d have only a little money, but we’d be happy.”

The following year, after another idyllic summer together at MacDowell, they eloped to Manhattan and set up house in Charleston. As someone from “Off”—and involved with the theater, to boot—Dorothy met with a chilly reception from the city’s Old Guard. But, by inserting herself into the ever-widening circle of writers and painters (who would create the Charleston Renaissance) and lending great emotional support to her husband, she gradually thawed the icy response. She persuaded DuBose to give up his work in insurance and devote himself to writing. It wasn’t easy: He struggled with his first novel, Porgy, the story of one summer of passion and loss, but Dorothy would not let him give up. When published in 1925, the novel ensured DuBose’s place in American literature.

Later, Dorothy helped her husband stage Porgy on Broadway, and, a decade after that, when George Gershwin expressed interest in adapting it as an opera, she convinced DuBose to keep after him until the great Tin Pan Alley songster followed through. After both her husband’s and Gershwin’s untimely deaths in 1940 and 1937, respectively, Dorothy kept the opera alive by lobbying tirelessly for its revival. She was responsible for the world tour in the 1950s that brought the work its long-overdue fame. And despite the prestigious Gershwin legend threatening to make the opera’s Southern roots all but forgotten, she continued to keep Charleston and the Heyward name a prominent part of the image of Porgy and Bess until her death in 1961. Dorothy became a kind of living memory of DuBose’s imagination, ensuring that the people of Catfish Row would survive them both for decades, perhaps centuries, to come.

J. Waties & Elizabeth Waring {1943-1968}

When J. Waties Waring, a federal judge with strong ties to secessionist politics, met Detroit native Elizabeth Avery Hoffman in 1943, it was unthinkable that they would fall in love, divorce their spouses, and eventually help pave the way for America’s civil rights movement. But the couple did just that, relinquishing social standing and personal safety for the advancement of racial equality.

In 1945, federal judge Julius Waties Waring was enjoying the privileges that his legal career and his birthright as an eighth-generation Charlestonian afforded. He and his wife of 32 years, Annie Gammell, lived as high society at their 61 Meeting Street house, and their life was the picture of propriety and decorum—at least to the public.

One evening in February, Waties came home from his chambers and told Annie that he had fallen in love with another woman. She was Elizabeth Avery Hoffman, whom the Warings had met two years prior when Elizabeth and her husband, a Connecticut textile magnate, began wintering in Charleston. Cocktail parties and bridge games evolved into more clandestine meetings between Waties and Elizabeth, leading to a decision that would astonish his peers and supporters. Waties asked Annie to move to Jacksonville, establish residency there, and grant him a divorce, as South Carolina did not allow the legal dissolution of marriage. Annie agreed, and soon thereafter Waties and Elizabeth were married.

Although the judge’s former pro-segregation politics had waned while he presided over federal courts in more racially liberal cities such as New York and San Francisco, his career veered dramatically leftward. Many attributed the change to Elizabeth. Born into a wealthy, liberal family, she had always been a progressive on race issues. Elizabeth urged her husband to be more conscious of his power and influence and to look at issues of race with more scrutiny and compassion.

During this time, Judge Waring made some bold legal moves. He ended the segregated seating of jurors in his courtroom, for instance, and in October 1948, appointed John Fleming, a black man, as his bailiff. His most dramatic ruling was the 1951 Briggs v. Elliot case, for which he declared the Clarendon County school board’s “separate but equal” doctrine unconstitutional, laying the groundwork for the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision.

Shunned by white society as pariahs, the Warings invited African Americans, such as activists Septima Clark and Ruby Cornwell, into their home—and paid a costly price. Someone burned a cross on their lawn; abusive mail spilled from the letter box; telephone calls began and ended with slurs and condemnations. Through all of this, Elizabeth stood by her husband steadfastly. “I’m with you, start to finish,” she told him, urging him not to back away from controversial cases or unpopular decisions. She bore the brunt of the community’s scorn. It was Elizabeth—aka “the Witch of Meeting Street”—wagging tongues declaimed, who had wrecked a marriage and ruined Charleston with her destructive politics.

When Waties retired in 1952, the couple moved to New York. “We were happy, the two of us,” he explained, but “you hate to be in a foreign land where you’re hated all the time, and that’s the way we felt we were.” From their apartment on Fifth Avenue, the Warings remained active in civil rights causes and stayed connected to political news in Charleston through their friends Cornwell and Clark.

Waties died in January 1968, Elizabeth following him just nine months later. Both were buried in Magnolia Cemetery, but not in the Waring family plot. His funeral was attended by 200 African Americans who paid homage to his achievements on behalf of racial equality. After his death, his daughter planted a magnolia sapling by his grave, but vandals uprooted the tree and cast it aside. Only nine people came to Elizabeth’s service.