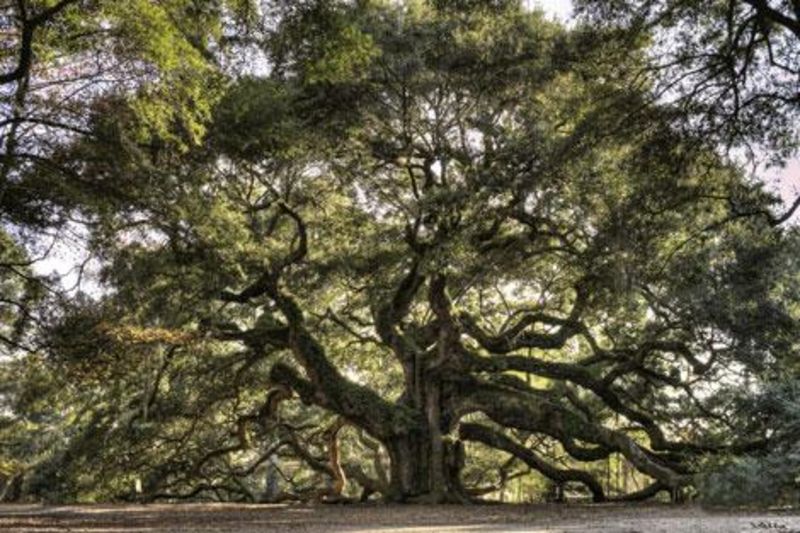

Angel Oak, John’s Island

By day, the Angel Oak is one of Charleston’s top tourist attractions, with visitors basking in the beauty of the Southern live oak that’s estimated to be between 500 and 1,500 years old—one of the oldest living things east of the Rocky Mountains, according to angeloaktree.org. But by night, colorful glowing lights and fiery apparitions of faces that can look part human, part goat or boar have been recorded.

A local couple who was married under the giant tree in 2008 returned to the site on a full moon many months later to recapture the moment in solitude. All around the ancient oak, they saw spirits. They described them as glowing human forms, around a dozen of them in different hues of light, gathered next to the enormous trunk, with several others up in the branches.

The husband, delirious in the experience, decided to carve a heart on one of Angel Oak’s branches with a pocket knife. As he put the blade to the tree, the paranormal display vanished. They began to hear things moving in the darkness. His wife asked that he put the knife away when she saw the bright flash of a devilish face that looked like it was on fire, a visage she described as a theater mask—part animal and part human. She spotted one more fiery face moving between the trees as the husband put his blade away. Hurriedly returning to the unpaved Angel Oak road, they looked back and saw the starry forms reappear.

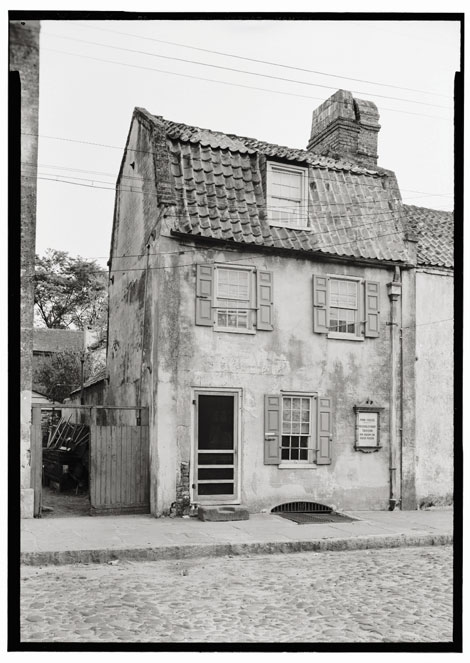

37 Meeting Street, downtown Charleston

Stolen jewelry, visions of a human silhouette, and droning cries for water late at night have marked the haunting of a pirate ghost at 37 Meeting Street. The spirit has surprised residents inside the gray Georgian mansion and in the backyard, appearing as a blurred image of a man with his arms folded across his chest.

Since the 18th century, stories of buried treasure have surrounded the prominent home, which in the days of pirates was waterfront property, as the creek (now Water Street) came all the way into what is now Meeting Street. And like most of Charleston’s pirate-treasure tales, the bounty never has been found under the house or in the yard.

One eyewitness, who grew up there, remembers seeing the apparition as a child in the 1970s. The ghost was blamed for jewelry missing from his mother’s powder room, having been heard creaking along the stairs while “snooping around.” The pirate’s spirit still lingers, stalking the plot of land where he might have buried his loot centuries ago or perhaps was hanged and, like Stede Bonnet, buried ignominiously beneath the low tide mark.

Magnolia Cemetery, located alongside the Cooper River on the upper peninsula, is the final resting place of many prominent Charlestonians, statesmen, and Confederate soldiers.

Magnolia Cemetery, located alongside the Cooper River on the upper peninsula, is the final resting place of many prominent Charlestonians, statesmen, and Confederate soldiers.

Magnolia Cemetery, Downtown Charleston

The wrought-iron gates of the peninsula’s Victorian-era Magnolia Cemetery open to a romantic, park-like setting—egret-inhabited lagoons, winding dirt roads, and grassy plots under the shade of massive oaks. There, among the thousands of graves, a local seer named Hope found herself drawn to the final resting place of two soul mates whose love story continues near the banks of the Cooper River.

The couple, whose names are withheld as a courtesy to their family’s privacy, has no epitaph. But their dates of birth, marriage, and death overpower any words. The woman was born in Charleston on September 27, 1861. Her husband-to-be was born September 27, 1863, at a Savannah River refugee camp. They married young and had seven children, including one set of twins. After the wife passed away on their 50th wedding anniversary, her husband grieved in a terrifying loneliness during the Great Depression. His death certificate reveals that his heart literally broke on February 9, 1933, the exact date that he lost his wife two years before.

The lovers remain in one another’s perpetual care on Green Hill, where Hope witnessed the couple’s spirits slowly waltzing under the oak canopy.

Fort Lamar Heritage Preserve on James Island, the site of the 1862 Battle of Secessionville; for more information and directions, visit www.dnr.sc.gov/mlands/

Fort Lamar Heritage Preserve on James Island, the site of the 1862 Battle of Secessionville; for more information and directions, visit www.dnr.sc.gov/mlands/

Secessionville Hollows, James Island

In the dark, early morning of June 16, 1862, Union forces launched an attack against the earthwork fort called Tower Battery on James Island. Although the Union troops outnumbered their Confederate foes three to one, a fierce, three-hour battle ensued, ending with the Federal retreat from the marsh and forested area. The sun rose over the bloody scene to reveal more than 150 bodies and nearly 900 casualties hobbling into the surrounding saltwater creeks.

Beyond the annual reenactments, the Battle of Secessionville can still be heard today. A paranormal replay exists in the muddy creeks and oak leaf hollows of the remnants of hastily constructed Confederate earthworks. James Island residents and visitors to the S.C. Department of Natural Resources-managed site have reported early-morning sounds—the metallic clicks of cannon fire resonate around the M-shaped Tower Battery at Fort Lamar, eerie thunks of something entering the creeks, and heavy splashes along the marshy banks as if injured soldiers are still fleeing the bloody scene.

Brick Kiln Ruins, Brickyard Plantation, Mount Pleasant

Alongside Wampancheone Creek, near the original Boone Hall Plantation and the ruins of a 19th-century brick kiln chimney, the startling image of a woman appears on the side of the road. Dressed in dark, ragged clothes, she moves her hands close together in repetitive thrusts, as if in a trance.

This apparition has only been seen at dusk. The longer the sunset, the more pale light passes through her image. All the sightings have occurred within 20 yards of one another. Because of her proximity to the kiln and creek, she is believed to be the ghost of an enslaved woman from an 18th-century industrial brickyard.

At its peak a decade before the Civil War, this brickyard was estimated to produce four million bricks annually with the labor of slaves from Boone Hall and other plantations along the Wando River. The constant repetition of molding the clay may have been what brought this spirit back to where she expended so much of her life and energy.

The ghost of a cadet purportedly haunts the Embassy Suites Hotel, formerly The Citadel Military Academy

The ghost of a cadet purportedly haunts the Embassy Suites Hotel, formerly The Citadel Military Academy

Old Citadel (Embassy Suites Hotel)

Meeting Street, downtown Charleston

Amidst the happy tourists and business folks bustling about Embassy Suites Hotel, a gory bit of history dwells. A spirit roams the halls and rooms of this building—the original Citadel, which was built in 1829 as an arsenal and later became the S.C. Military Academy. Because of the unchanging style of cadet uniforms, it would be difficult without a detailed investigation to determine from what century he hails. Yet there is one common denominator to this ghost—the top of his head is missing.

From varied descriptions, whether from stunned housekeepers or the cardiologist who left screaming in her underwear upon an early-morning encounter, it seems his skullcap was shaved off right above the brow. Since this lost cadet, also known as “Half-head,” was first documented by paranormal researcher Ed Macy, he has become a celebrity. Last October, The Huffington Post declared that this ghost made Embassy Suites “The Most Haunted Hotel in the South.”

Fort Moultrie, Sullivan’s Island

On Sullivan’s Island, between Stella Maris, the Catholic church known by mariners as the “Star of the Sea,” and the still active lighthouse, lies the historic Fort Moultrie, where a pelican bird—part of this world and part of the supernatural—dwells. The seabird, said to be the spirit of Seminole leader Osceola, roams the gravesite of his headless skeletal remains at Fort Moultrie.

Osceola, née Billy Powell, was born to a Creek Indian mother and Scots-Irish father in Alabama in 1804. After the Creek War, he and his mother moved with their tribe to Florida and lived among the Seminoles, who named him “Osceola,” or “Black Drink Crier,” after the ceremonial black cassina tea used as a ritualistic purge before going into battle. He later became a war leader against the Federal removal of the Seminole from Florida. Osceola was seized at the height of resistance in late October 1837, while under a flag of truce at the camp of General Thomas Jesup. He was later transported to Fort Moultrie, where he died from a throat infection on January 30, 1838. There, the attending doctor decapitated the warrior’s corpse and embalmed his head “for further study.” Passing through many hands, the skull was donated to the Medical College of New York, which was destroyed by fire in 1865.

Back on Sullivan’s, Osceola’s spirit bird has been spotted perched in the palmettos and myrtle thickets along the beachfront, as well as on the fort’s grassy embankments and windswept parapets. At first glance, the pelican appears commonplace, but it has been seen in flight, spilling drops of black liquid across the burial grounds.

The Wampee House, Pinopolis, Berkeley County

With its well-documented history of paranormal phenomena, many have called the Wampee House, a circa-1822 Lowcountry plantation home, the most haunted place in Berkeley County. Built on the Wampee Plantation property, the present house is the third on the site, which was acquired by Santee Cooper prior to the building of Lake Moultrie.

There is a cold spot in one of the bedrooms where the caretaker’s dog will not go. Tiny white lights have been seen moving across the porch. The sounds of doors opening and closing for hours on end have kept Santee Cooper board members up throughout the night. A visiting New York businessman awoke once to see a face hovering above his bed. The events are too many to list but have led some to hypothesize that the ghost is that of an Indian maiden who lost her life following her mate into battle with European settlers.

In one of the Indian mounds on the property, excavated for The Charleston Museum several years ago, the remains of a woman, buried in a crouching position, were unearthed. Little is known of her history, but the spirit of a woman with what has been described as a porcelain face was witnessed at the Wampee House shortly after the excavation. The ghost has been seen visiting every room of the residence and all around the surrounding premises, vanishing as mysteriously as she appears.

The name “Wampee” is thought to be an Indian word for pickerel weed, an aquatic plant with a blue flower found growing in low mashy areas. The Wampee House ghost is said to wear a garment of flowing blue silk, seemingly made of these blooms, with matching slippers.

One caretaker of the plantation house had a close encounter with the ghost as she was putting china away in the main dining area. The light was fading and from the corner of her eye she noticed a figure out on the piazza. She turned and saw a clear image of a young Indian woman dressed in buckskin and ribbons looking directly at her through the window until it slowly disappeared with the setting sun.

The Pink House

17 Chalmers Street, downtown Charleston

Nobody knows who the spirit belongs to. She could be as dated as the late 17th-century structure itself, which was hand-built of Bermuda stone, a West Indian coral stone with a natural pink hue. Previously a gallery, the Pink House is one of the few remaining intact buildings of the old walled city of Charles Towne.

Three former Pink House owners, who filled the tiny dollhouse-looking space with art for more than two decades, believe the ghostly photographs captured by patrons may reveal the different life phases of former tavern owner and famed female pirate Anne Bonny. She is said to have resided on the third floor and run her popular business on the floors below.

Windows have opened suddenly on hot summer evenings, and soft footsteps have been heard climbing the stairs as well as the sibilant sound of a dress flowing. One visitor said he felt the overwhelming sense that someone was peering at him from the stairwell. When he looked up, nobody was there.

Joe E. Berry Residence Hall,

College of Charleston, downtown Charleston

The young ghosts that haunt the College of Charleston’s Joe E. Berry Residence Hall are as mischievous as they are mysterious. This contemporary building constructed in 1988 rests on the former site of the Charleston Orphan House, the first publicly funded orphanage in the United States. The five-story facility, built on Boundary Street (now Calhoun) to support and educate the city’s poor, white children, initially served 115 kids, with enrollment peaking at 334 children shortly after the Civil War.

According to Orphan House records, its infirmary was full during the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918. The children who were not sick had unattended play yards to themselves. It is said they made tents from cardboard found in the trash, and, after a while, became bored and raided the kitchen. They brought back an oily rag and lit their tents on fire. The dark smoke billowed into the open windows of the infirmary. During the evacuation of the building that fateful night, one can only speculate how long it took to remove more than 200 sick children. Four orphans between the ages of eight and 13 passed away of smoke inhalation.

The Charleston Orphan House building was demolished in 1953 to make way for a Sears Roebuck store, and the institution moved to its new campus in North Charleston. The department store was short-lived and became the property of the College of Charleston.

Since the dorm’s opening, students have been plagued by a rash of false fire alarms, as well as the distant voices and laughter of children late into the night. The eerie sounds travel through the halls, stairwells, air conditioning vents, and under the trees on the outer brick courtyards between 2:30 and 5 a.m. Many have been awakened by the sound of marbles cascading across the floor, only to find none.

The disembodied voices heard are generally described in interviews as eerie, but celebratory. A few witnesses noted hearing the high-pitched chanting of a popular children’s game, “Ring Around the Rosie.”