Hollow cheeks. Kaposi’s sarcoma sores. Gaunt gay men wasting away. Thankfully, the haunting images from the AIDS heyday of the late 1980s have nearly faded into a distant, morbid memory. Twenty-six years after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention first officially named and defined “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome,” the disease that was once a terrifying death sentence rarely makes today’s headlines. Now that new medicines have drastically improved prognoses and quality of life for those with HIV/AIDS*, the disease is out of the limelight. Tom Hanks in Philadelphia is relegated to the dusty bottom video store shelf, and the once ubiquitous red ribbon, the international symbol of AIDS solidarity, has been edged out by the softer, sexier pink ribbon for breast cancer. A quick and totally unscientific poll of Farmers Market shoppers one cool fall Saturday at Marion Square—a random sampling of dog walkers, young professionals, and fresh vegetable buyers, all Caucasian—reveals some local perceptions and questions about HIV/AIDS today: “It’s mostly an African problem.” “We’ve got a handle on AIDS in the U.S. Third World countries are where it’s rampant.” “HIV is still around, but I don’t think it’s an epidemic.” “Is HIV the same thing as AIDS?” “Maybe it’s a problem in big cities, with gays and IV drug abusers, but not so much here.” If only that were so, wishes Brad Childs. Childs’ world is only seven miles north of Marion Square, off Dorchester Road in North Charleston, where he and his staff at Lowcountry AIDS Services (LAS) see a much different reality. The phone lines stay busy; the offices (former patient exam rooms in this repurposed ob-gyn office) house four full-time caseworkers, a case supervisor, and a prevention specialist. “I would love to be out of a job,” says Childs, but instead, in his fourth year as director, he’s wrapping up a $2-million capital campaign to expand LAS’s services and ensure the nonprofit’s stability and longevity. HIV/AIDS may no longer be the alarming media darling, a celebrity cause du jour, but it certainly has not gone away. If anything, the fact that it has begun to slip off the public’s radar means HIV/AIDS is becoming ever more a threat, especially in the South. Disturbing Disproportion Here in the Lowcountry and across America, the face of AIDS is changing. No longer primarily a gay man’s disease concentrated in urban areas like San Francisco and New York, HIV/AIDS is increasingly rural, black, and female, and more and more it speaks with a Southern accent. The Southern AIDS Coalition’s 2008 “Manifesto Update” reports that nine of the 15 states with the highest new HIV diagnosis rates are in the South, home of more than 40 percent of the country’s new HIV infections. Of the nation’s top 20 metropolitan areas with the highest AIDS case rates. in 2006, 80 percent are in the South. From 2001 to 2005, AIDS deaths declined or held steady in other regions of the country, yet they rose 14 percent in the South. And while the region comprises only 36.4 percent of the U.S. population, it accounted for half of the nation’s AIDS deaths in 2005 and more than half of the people living with HIV in 2006. A disproportionate number of those with HIV/AIDS are black. In the modern manifestation of the epidemic, African Americans, while representing only 12 percent of the U.S. pop-ulation, become infected with and die from HIV/AIDS more than any other racial or ethnic group: 47 percent of the country’s newly diagnosed HIV/AIDS cases in 2006 were among blacks. African Americans represent only 19 percent of the South’s population, but more than half (58 percent) of new AIDS cases reported in the South in 2006 occurred among this group. Infection rates among black women continue to be high; in 2002, HIV/AIDS was the leading cause of death among African American women aged 25 to 34. The infection rates in South Carolina and in Charleston reflect these national and regional trends. “South Carolina ranks ninth in the country in terms of incidence of HIV/AIDS,” notes Childs, dismayed by the statistic that keeps him in business. Sixty-one percent of newly infected South Carolinians are black. “The minority population clearly bears the brunt of infection in this state,” says Preston Church, MD, an associate professor of medicine and infectious disease specialist at the Medical University of South Carolina. Close to 75 percent of South Carolinians living with HIV/AIDS are African American. “What’s interesting is that the situation in South Carolina in some ways mirrors the situation in sub-Saharan Africa or the Caribbean,” notes Church. “This is not just a disease of injecting drug abusers or men having sex with men.” While those traditional risk behaviors continue to result in HIV transmission, we’re seeing more women become infected after having sex with men who may have been infected by other men. It’s a domino effect, essentially, explains Childs. “Anytime someone has unprotected sex without knowing their partner’s HIV status, he or she is at risk, especially if they have multiple partners.” As a result, women represent about 40 percent of the infected population in South Carolina, and the huge majority of those are African American. Causes & Concerns, Progress & Challenges Several factors play into the increasing incidence of HIV in the Southern, rural, minority community. Childs sums up the crux of the crisis in three words: “‘the down low,’” he says. In South Carolina, HIV infection is almost exclusively transmitted sexually—only a very small percentage is related to intravenous drug injection—and in the African American community, he says, men tend to hide their sexuality, keeping their encounters with other men on the “down low.” “These men then go on to infect their wives, girlfriends, or other women.” High poverty rates, inadequate education and housing, high incarceration rates, and lack of access to and distrust of the medical system also correlate with increased HIV rates among African Americans. Similar issues also play into the growing incidence of HIV in the South’s Hispanic community, where language barriers and fear of deportation among illegal immigrants add to the challenges of getting HIV testing, treatment, and care. The good news is that with the new, highly active antiretroviral medications, HIV/AIDS has become more of a chronic illness than an acute one, says Valerie Assey, RN, MSN, an MUSC faculty member who has worked with the Infectious Disease Clinic since helping establish it in 1991. Therapies are simpler today: patients can sometimes take just one pill instead of the 20-plus pill “cocktail” prescribed a decade ago. Yet these new antiretrovirals are often difficult for patients to tolerate, and incredibly expensive, averaging from $900 to $3,000 a month. The state provides a drug safety net for uninsured low-income people through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), established by the federal Ryan White Care Act; however, funding for this program is dependent on federal and state dollars. “We do still see patients on all sides of the illness spectrum, but generally, if people regularly get care and take their medicines, they can stay healthy and lead vigorous, normal lives. If they don’t take the medicines consistently, they can develop drug resistance,” adds Assey. The length of survival for HIV patients on antiretroviral medication today is about the same as what most noninfected adults can expect and hope for—but if untreated, HIV life expectancy can be as little as five to 10 years from date of diagnosis. Getting tested and knowing your HIV status is key to fighting this epidemic, agree experts like Assey, Childs, and Church. People typically change their risk behaviors once they know their status. “Unfortunately, we don’t do well diagnosing HIV until people are sick, so we’re missing an opportunity for early intervention,” says Church, who estimates that 25 percent of undiagnosed HIV carriers result in 50 percent of new cases in South Carolina. “Prevention, education, and awareness are the only way we can turn around this epidemic,” says Childs, who emphasizes that current prevention resources are minimal. South Carolina only receives $1 million for prevention services, administered statewide through DHEC, of which LAS receives $100,000 for its testing, outreach, counseling, and prevention/intervention budget. To address this, LAS, through its capital campaign fundraising efforts, is putting more resources into a prevention/education and public relations push. As a result, LAS has doubled the number of people being tested at their North Charleston office and at multiple testing sites they offer throughout the community. “HIV/AIDS can happen to any of us. This disease knows no social boundaries, no economic boundaries” says Childs. “One wrong move and you could be infected. It could be your child, your wife. My own family from Charleston didn’t think it could happen to us until it came knocking on our door,” adds Childs, whose 30-year-old brother died of AIDS in 1984. Despite progress in testing and treating HIV/AIDS, the stigma related to the disease is still alive and well and continues to be a roadblock both for people dealing with the disease, and for prevention efforts in rural and minority communities. “There’s still such huge discrim-ination when it comes to jobs, housing, and medical care,” says Aaron Dunn, a caseworker for LAS. “We see it every day, people who are shunned by their landlords or their families.” One client, a 20-year-old African American woman, was thrown out of her home after she told her parents she was HIV positive. LAS provided housing assistance, “otherwise she would have been homeless,” notes Childs. In his daily interaction with clients, Dunn does everything from delivering groceries to clients to taking them to doctor’s appointments to counseling. He has an average caseload of 180 clients and runs several support groups at LAS, averaging 25 to 30 people per session. “This is the most challenging job I’ve ever had but also the most rewarding,” says Dunn. “I never take it for granted that sometimes the best medicine is just being loved and accepted by someone who is not judgmental.”

age 35, Charleston As a teenager in the small Mormon farm valley of Preston, Nevada, Andrew had clear motivation for raising two pigs and coordinating the meat-judging contest for a state agricultural conference. “It got me to the big city,” he explains. “The Future Farmers of America conference was in Reno, and Reno had a Benetton store. I was 18, and I was in love with Benetton.” After college, Andrew realized his dream of moving to New York, where he worked in fashion and makeup. “I went from being president of Future Farmers of America to professional makeup artist,” he laughs. “That was probably harder for my parents than accepting that I was gay.” In 2000, he came to Charleston as a regional artist for Trish McEvoy, a leading cosmetic brand carried by Saks and Gwynn’s of Mount Pleasant. A man of natural warmth and charm, Andrew finds teaching women about makeup rewarding. “I love that I can help empower women, give them confidence. They leave feeling great about themselves.” However, in late fall of last year through early spring, Andrew didn’t feel so great himself: he had major fatigue, difficulty breathing, and was frequently sick. “I had always been monogamous, very safe,” he says, “but there was a period when I foolishly put myself at risk.” Andrew was terrified he had AIDS, and on March 24, he finally went to LAS to get tested. His fears were confirmed: he was HIV positive; his T-cells were dangerously low and his viral load sky-high. By April, he had lost 20 pounds with fevers reaching 114 degrees. “I was taking a ton of meds, including three different antibiotics. Quite honestly,” he says, “I thought I was going to die.” Andrew regrets waiting so long to get tested, especially because he selfishly put others at risk (they’ve since tested negative). “I lived in denial; I didn’t want to know,” he says. “I was scared I might lose my job, afraid I’d be ostracized. But knowing is so much more amazing than being afraid. There’s a freedom that comes from knowing. Before, I couldn’t start relationships with people because I couldn’t be honest.” Andrew is grateful for what he feels is a second chance. Without modern medicines, he acknowledges, “I’d almost certainly be dead.” His energy is back, his viral load and T-cells are out of the danger zone, and he’s experienced “no judgment, nothing but compassion” from colleagues, friends and family, his doctors, and the folks at LAS. “I’m still overwhelmed by how really amazing and supportive my clients and colleagues have been,” Andrew says. “They listen when I’m scared and shower me with strength when I’m feeling weak. They believe, as I do, that the past can’t be changed, but how we act in the future is what matters. “HIV does not discriminate,” Andrew adds. “I don’t ask ‘Why me?’—I know why me. If I’m going to live out my life, it’s going to be an open and honest one. I don’t want anyone else to die from something that can be prevented. Instead of dwelling on the negative aspects of being (HIV) positive, we can help others stay negative, and that is going to take a great deal of honesty and communication.”

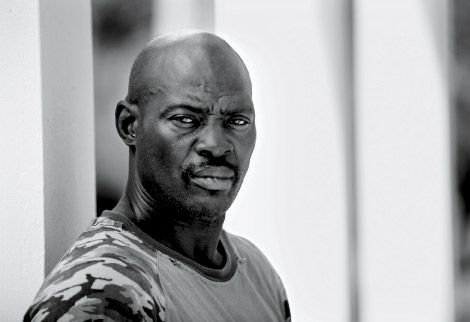

age 54, North Charleston “I was diagnosed in March,” says Ernest, a school custodian in North Charleston, where he’s lived all his life. “I went to the health department, got tested, and it came back positive. I knew it would. After I found out my wife had it, I knew I had it. But I didn’t find out she was infected until I went with her to her mental health counselor—she’s the one who told me, not my wife. We’d been married nine years, and I never did know she was infected.” A no-nonsense, upbeat guy who has known some hard knocks, Ernest has a positive outlook about his HIV status. “It hasn’t changed my life,” says this father of nine and grandfather of 10, who is robust and healthy and not currently taking any HIV-related medication. “I know a lot of people with HIV. I take it day by day; I don’t worry about it. I go to my [support group] meetings on Thursdays, and everybody there go day by day, too. Everybody got different stories: some been diagnosed for 10 years. It’s a disease you live with like any other disease you get,” he says. “Like cancer or high blood pressure.” Despite having HIV, Ernest feels like he’s in a good place, with support from his kids and from Aaron Dunn, his caseworker at LAS, and his Health Department social worker. “It’s good to have people in your corner,” he says. “I leave here [LAS] feeling good. I got the best support in the world.” A former crack cocaine user, Ernest has been clean for two-and-a-half years and is now separated from his wife, who continued to abuse drugs while refusing HIV treatment until she got sick. He now lives with a girlfriend who is also HIV positive (infected prior to their relationship), but he regularly checks on his wife and their nine-year-old daughter, whom he keeps on the weekends. “I go cook for them, make sure my wife takes her meds. She’s real weak, weighs maybe 50 pounds now, and can hardly walk. It hurts when you see that—when you see what AIDS can do. My wife stayed in denial and didn’t take her meds, and drinking and drugging makes it worse. It’s hard to see that in people you care about,” Ernest adds. “It makes you really want to take care of yourself.” Taking care of himself and others means being open about his HIV status. “You don’t know who got what now, ’cause nobody talking,” Ernest asserts. “Everybody holding it in. My wife didn’t tell me. The girl I’m with now—her boyfriend had HIV and didn’t tell her, and he’s dead now. You got to be open, get tested, talk about it, and understand what it’s all about. I won’t go infect anybody else,” he adds. “If I change partners, we got to talk and use protection. Can’t hide it,” Ernest asserts, “because then you’re messing up the next person’s life.”

age 60, Summerville As a child growing up in rural Louisiana, Kathrin knew her younger brother Reece was different. “He liked us to dress him up like a girl. Once he got shot by a pellet gun and had to go the emergency room wearing a dress and scarf,” she laughs. Decades later, Kathrin was back with Reece at the hospital under less humorous circumstances: her gay brother died of AIDS at age 37. In 1995, four years after Reece’s death, Kathrin learned she was HIV positive. “I used to donate plasma because I had a titer factor that was good for burn patients and because I needed the money,” says the mother of two and ex-military wife, “and one day they rejected me. They sent me to the health department for an HIV test. I cried for a week,” Kathrin recalls. After her divorce, she’d become infected by a man she’d known for 17 years. “I knew he was high-risk, but I didn’t think about it in the ‘heat of the moment,’ so to speak,” she says. She has been celibate since being diagnosed. Kathrin carries a blue bag full of medicine with her everywhere. “Twice a day, like clockwork,” she says as she easily rattles off seven or eight tongue-twisting prescription names, only two of which are specifically HIV-related. She can tell you exactly what every pill is for, a familiarity she attributes to her 16 years working as a shift supervisor for a pharmacy before being let go, a termination she views as HIV discrimination. Kathrin qualifies for disability for mental health reasons, and that plus Medicare/Medicaid coverage pays pharmacy bills that otherwise would cost her more than $2,000 each month, about $1,000 more per month than she lives on. Her younger son, currently unemployed, lives with her, and her lack of transportation makes it difficult to attend LAS support group meetings. “Otherwise, I’d like to go,” she says. Kathrin’s budget may be tight, but her spirits are high. “My health is wonderful; I’ve never been sick from something to do with HIV. My virus stays pretty much undetectable,” says this scrappy, articulate woman whom LAS caseworker Aaron Dunn dubs “a survivor.” “If I dwelt on the HIV and did nothing but take all these medicines, I would just be a hermit,” Kathrin says. “But I like to walk, go to the grocery store, and do crafts and jigsaw puzzles. I try to get to church every Sunday, and they usually have food there: food for the spirit and the body. I’m just making it,” Kathrin admits, “but I feel like I cope pretty good. I tell people there are no pity parties and no word named ‘can’t’. The ‘what-ifs?’ They’ll have to wait.”