Samuel F. B. Morse (yes, that Morse) was once Charleston’s most fashionable portraitist

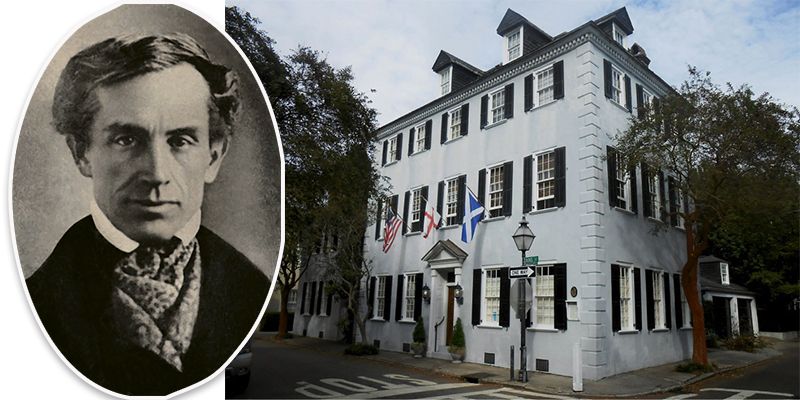

(Left) Samuel Finley Breese Morse in 1840; (right) For a time, Morse kept a studio at 94 Tradd Street.

We know Samuel Finley Breese Morse as a coinventor of the telegraph and Morse code, but often overlooked is the fact that the man was also famous as an artist, one of the great portraitists of his time. And from 1817 until 1821, Morse spent his winters working in Charleston, painting portraits of the city’s finest.

The Massachusetts-born genius was only 26 and still unmarried when he arrived here in the fall of 1817. He came with well-placed letters of introduction—his father, Congregationalist minister Jebediah Morse, was a friend of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Morse had also studied in England with his mentor, painter Washington Allston, of the wealthy Georgetown/Waccamaw River rice-planting family. His maternal uncle, Dr. James E. B. Finley, was one of Charleston’s more notable physicians, and for a time Morse lived with the Finleys in their home at 19 King Street near the Battery.

His portrait of President James Monroe is displayed in Charleston’s City Council chamber.

Morse could not have picked a better time or place to kick-start his artistic career. Rice and cotton had created a booming economy driven by a wealthy, educated elite who had both money and an eye for artistic excellence. Some, like Morse’s most stalwart patron, John Ashe Alston, had homes that were virtual museums of fine art collected on European tours. Given his talent and likeable personality, Morse was welcomed into this silk and satin society with open arms—and pocketbooks. He had been lucky to nab $15 for a portrait in New England. By the end of his first year in South Carolina, he was getting $80 for each one. As of January 1819, Morse had banked $3,500 worth of commissions (some $60,000 today), with more in the offing.

The artist slipped easily into Charleston’s elegant lifestyle, yet his no-frills New England upbringing sometimes clashed with the city’s gregarious society, particularly on Sundays. “Oh, what a different Sabbath from our quiet, heavenly Sabbaths in New England,” Morse wrote his fiancée, Lucretia Pickering Walker, in New Hampshire soon after his arrival. “The people of fashion employ this day in visiting and in dinner parties. It is the most common day for paying calls; the result of all this is that the day of rest is a day of universal confusion and bustle….”

Morse and Lucretia were married in 1818 and in mid-November arrived in Charleston for the winter—a busy, highly social season when plantation families came to their town houses for the whirl of balls, horse races, and gala entertainments. For $10 a week, the Morses lived with Mrs. Katherine Munro at her 95 Church Street boarding house. Morse moved his studio from King Street to the back of the Barelli & Torres store at 65 Broad, which was reached through a private entrance from St. Michael’s Alley.

In subsequent years, Lucretia and the couple’s children would stay at home in New Haven, Connecticut, while Morse spent the “season” in Charleston. He had an untiring work ethic, holding as many as four sittings a day, during which he captured the nuances of the subject’s expressions, saving the painstaking detail work for later. In some cases, such as full-length portraits, he would take canvases back home to Connecticut to finish during the summer.

Morse’s 1818 portrait of Dr. Alexander Barron hangs in downtown’s Waring Historical Library.

Morse was not the only major artist in Charleston at this time. Some 13 other painters were working as well, enjoying various levels of success. They included the miniaturist Charles Fraser, whom Morse had known since both were students at Yale; landscapist and fellow Bostonian Alvan Fisher; portraitist William Shields; and Benjamin Trott, famous for his animal paintings. But when it came to obtaining commissions, none were a match for Morse, who soon became the most fashionable and highest-paid portraitist in town.

Morse’s clientele was the proverbial “anybody who was anybody.” Among them were General Thomas Pinckney, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, and Colonel William Drayton, as well as members of the Grimke, Hayne, Huger, Bacot, Ladson, Beach, Ball, and LaBruce families, to name just a few. His portrait of President James Monroe, commissioned by the city in honor of the leader’s visit to Charleston in 1819—the first presidential visit since Washington’s—remains a focal piece in the art gallery in the City Council chamber today.

For various reasons, particularly an economic downturn that greatly diminished commissions, Morse did not return to his Southern honey hole after the 1821 season. He was in Washington, D.C., in February 1825, working on a life-size portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette, when he received news from a messenger on horseback that Lucretia had died suddenly, not long after the birth of their third child. She was buried before he could reach their home in New Haven. Grief stricken, he would eventually devote himself to finding a better way for people to correspond across long distances. The result was, indeed, history. His role in inventing the telegraph and Morse code transformed communications forever.

Photographs courtesy of (3) Wikimedia Commons & (Dr. Alexander Barron) Waring Historical Library, MUSC, Charleston, S.C.