For those who were in Charleston in the weeks following Hurricane Hugo, there are a number of sights, sounds, smells, and emotions that will remain forever imprinted in our collective memory. These are things we’ll never forget:

The smell of fresh pine. It was intense, like someone poured Pine Sol on your head. While at first the scent seemed odd and out of place, the reason for it dawned on us fairly quickly—a million pine trees had just exploded simultaneously.

The sound of chain saws. The second day after the storm, the saw engines revved up and seemed to never stop. It became a sound so common one ceased to even notice it. If you were anywhere within the Tri-County area, you heard chain saws every day—dawn until dusk—for two months.

The smell of outdoor grilling. Electricity vanished for at least two weeks. Before long, it occurred to everyone that those frozen fillets and shrimp weren’t going to do so well in a room-temperature “freezer,” so out came the goodies. We grilled the bounty on the front lawn and shared it with neighbors.

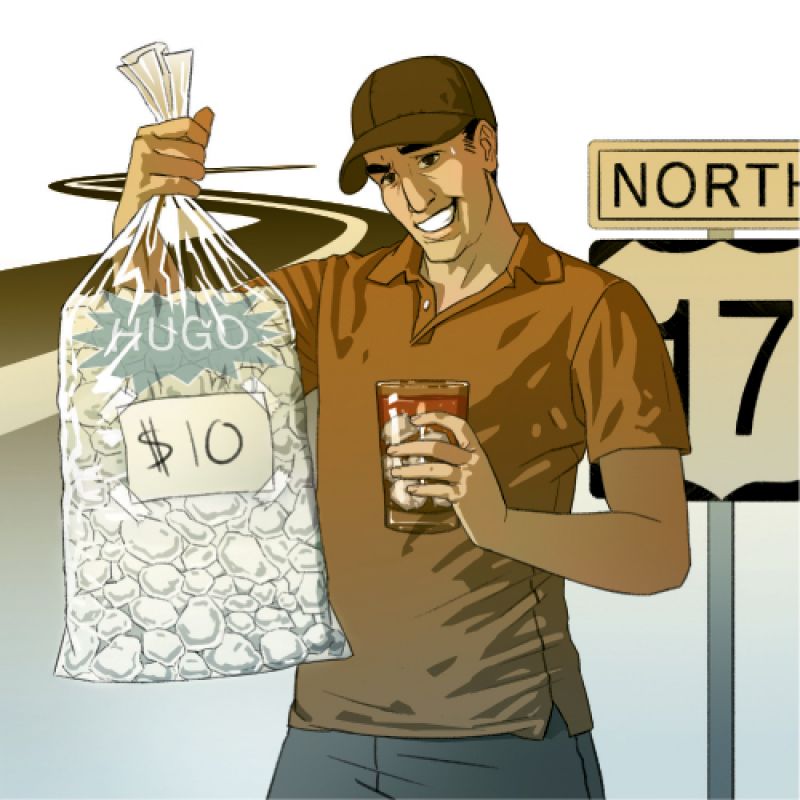

The sight of “gougers” along Highway 17. The sign read “Ice. 10 Lbs. $10.” I’d never been so happy to see a sign in my life. $10? We’d have paid $50. Happily. I laugh when I hear about the police turning back “gougers” from disaster areas. If “gougers” aren’t going to bring the ice, chain saws, generators, and bottled water, then who is? The federal government?

The feeling of camaraderie. No one stopped working until their neighbors, family, and friends were cut free from the wreckage and had a place to live. The city governments rose to the occasion brilliantly. Utility trucks poured in from all over the country. I saw a fire truck flying the Texas state flag. Everyone mattered, and everyone pitched in.

The sight of tidemarks—inside. When we got to my grandmother’s home on Gibbes Street, the water line left by the tidal surge was six feet high. Not knowing what else to do, we got the hose and began spraying the pluff mud off a dozen 300-year-old antiques. You can still see tidemarks in some homes, kept for posterity.

The sounds of local news reports. We were, for all intents and purposes, living in the late 1800s with the exception—thank God—of battery-powered radios and televisions. Our only connection to the outside world was local news, and the various teams did an amazing job. One of our favorite evening rituals was to tune in to Live 5 News to see if Bill Sharpe had shaved yet. Bill, you are still the man.

Reading the first post-Hugo issue of The News & Courier. It was printed far faster than anyone thought possible—I don’t recall the number of days—and filled with information needed by the public. One of the articles I found brilliant: How much you should pay to have trees removed. Prior to this piece, tree-removal crews had arrived into town from hundreds of miles away and really were gouging people—charging 10 times the normal rate. Think we were being gullible? Walk out into your own yard, cut down every tree, and (without Google) try and guess how much it would cost to have them cut up and removed. That single article saved residents hundreds of millions of dollars, because insurance companies covered the real cost—not the gouged cost.

The taste of adult beverages. Although we lived like the Waltons and labored sun up until sunset—well, this is Charleston. And since the average home has a six-month supply of booze, our evening entertainment was a foregone conclusion. If you wondered why we were willing to pay $10 for a bag of ice, now you know.

Seeing houses tagged graffiti-style with names and numbers. Tens of thousands of locals’ homes were unlivable or essentially gone—and cell phones were still those briefcase-size contraptions only used by the Gordon Gekkos of the world. As a result, people spray-painted their insurance company’s name and a phone number where they could be reached on the front of their houses.

Hearing the phrase, “How’d you do?” The standard answer among residents, unless your house was completely gone, was, “Pretty good. How about yourself?” I remember, two months after Hugo, my dad and I meeting with an associate from Charlotte, who gushed with awe at the $100,000 damage his company’s building sustained. Finally, in order to move on, Dad said, “I had five times that done to my home.”

Discussing insurance technicalities. Within a month, everyone in Charleston was an insurance expert. I’m talking actuary-level insight. One of the key points of conversation was, “Did you have contents?” If you can’t feel the pain of that question, you weren’t here.

Like it or not, you’ll find a certain callousness among Charlestonians when the national news reports on the latest natural disaster and rages against the government’s slow response. Or the fact that “not enough resources” have been committed. Why? Because if the Feds ever showed up in the Lowcountry, no one I know ever saw them. I’m told they started helping after two weeks, but in the I’m-not-making-this-up category, the Junior League of Orlando was here serving meals in less than one week.

We banded together, put on our big-boy underwear, and reclaimed our lives—every man, woman, and child. The various city governments did Herculean work and didn’t worry about the budget. The cops busted heads when people tried to loot. Electrical crews worked 24/7. And it never occurred to anyone to whine.

Why? Because this is Charleston. And that’s how we do things here.