October 2022

Written by Stephanie Hunt

Images by Portraits of Drew Doggett by Mira Adwell; All other Photographs courtesy of Drew Doggett

The dust jacket of Drew Doggett’s latest book, Wild: The Legendary Horses of Sable Island, gives your first clue: “Sable Island is home to one of the last herds of completely wild horses—and nothing else.” Those last three words are part of what distinguishes the Mount Pleasant-based fine art photographer. The handsome, hefty tome, complete with a foreword by renowned primatologist and anthropologist Dr. Jane Goodall, features more than 100 large-format photographs of the island’s gorgeously feral horses, with their dreadlocked manes and steely, knowing eyes, in muscular romps across the dunes. Each image is astonishing—the animals alluring and charismatic. But beyond his equine subjects, Doggett’s lens captures the island’s breathtaking nothingness with equal gravitas, equal everythingness.

Sable’s immense silence, punctured only by wind and the occasional thrum of horse hooves, is amplified in every frame. Its remoteness, isolated 152 miles off the shore of Nova Scotia, is palpable as the untrammeled majesty of mere dune and scruffy grass comes into focus. Doggett transports the viewer to an otherworldly realm of rugged grace and raw magnificence. Whether he’s shooting solo for weeks at a time on the Captain Sams Spit-like crescent of sand that is Sable Island, or on the plains of Ethiopia and East Africa, or the hinterlands of the Himalayas, Doggett’s subject matter is all that is wild and wondrous; his aperture is that of amazement.

Catch up with the globe-trotting photographer in the studio behind his I’On home, however, and things are a bit more domesticated. Abandoned beach and yard toys lie in a pile under some shrubs—evidence of the suburban wilderness known as parenting. Doggett, 38, and his wife, Kristin, a former event planner pursuing her masters in social work, moved to the Lowcountry in 2015, after nearly a decade in New York City, where he cut his teeth as a photography assistant, working mostly in fashion (we’ll come back to that). “We longed for a yard, and we wanted to spend time on the water, not just look at it,” says Doggett, who grew up in Potomac, Maryland, as did Kristin, his high school sweetheart. His family of fifth-generation Washingtonians spent summers on the Chesapeake Bay. “I gained such a sense of independence by spending time on the water, sailing our Hobie Cat across the bay with my brother,” Doggett says of his earliest “expeditions.” He and Kristin, a College of Charleston graduate happy to return to the Holy City, wanted that same type of experience for their kids, five-year-old daughter, Emerson, and son, Graydon, four.

Though Mount Pleasant is far removed from the studios and fine art galleries of New York, the landscape of family life, and of the Lowcountry, has brought Doggett’s artistic mission into sharper focus. “I’m driven by a sense of urgency, a wish for my children to experience these incredible places, these creatures and cultures,” he says.

Places like Sable Island, where herds of wild horses have survived for some 300 years; however, with more humans being allowed to visit and sea levels on the rise, that will likely change. Places like Kenya, where the incredible majesty of super tusker elephants, (those with tusks weighing a combined 200 pounds or more), the subject of Doggett’s “Colossal Shadows” series, may soon be lost to future generations. Only 24 of them are currently walking the earth—giant remnants of another realm, emissaries from an animal kingdom under duress.

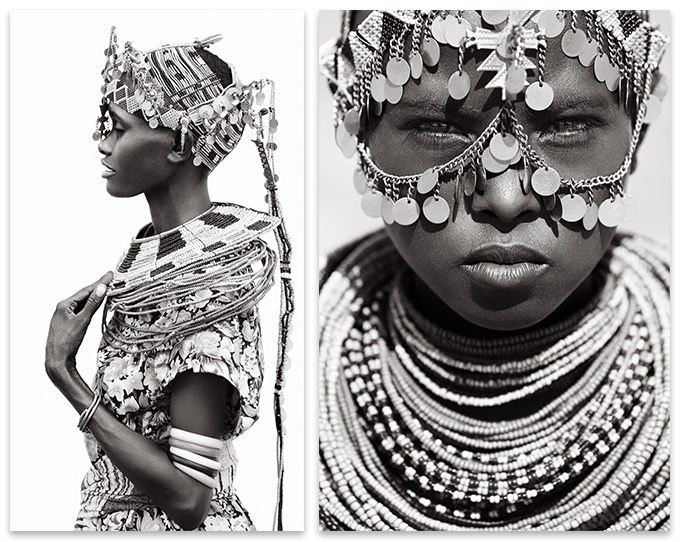

Doggett’s body of work not only documents these sublime and vulnerable creatures, it parlays the preciousness, the natural wonder, of all that is at risk. If Emerson, Graydon, and the rest of us are now living in the Anthropocene, Doggett is leaving photographic bread crumbs of a wilder, more untouched world, a world not ours, but theirs—the uncoiffed horses, the ivory-laden tuskers, the regal big cats of India, plus the myriad other subjects, like Kenya’s intricately beaded Rendille and Samburu warriors, he has traveled the world to photograph.

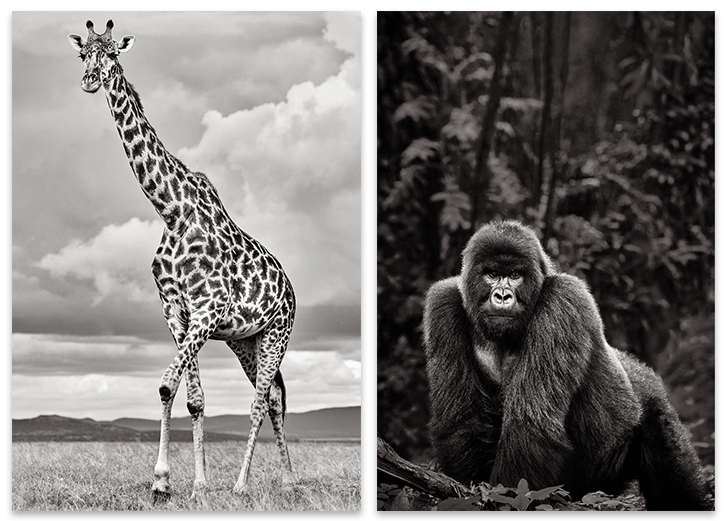

Out of Africa: For his “Exceptional Creatures” series, Doggett documented the majestic beasts of the African plains as well as endangered wild species on other continents. The connection he felt to wildlife and adventure on a college graduation trip to Africa inspired his later career shift.

Fashion Forward

Doggett’s journeying to the far reaches of distant continents began as an undergraduate at Vanderbilt University, where he studied human and organizational development while also nurturing an interest in photography, a hobby he picked up during high school. “One of the requirements for my major was picking an organization to study. I chose Gomez Photography and Westlight Studios in Nashville,” says Doggett.

His school project turned into an internship with Michael Gomez, a leading portrait photographer, well known for album covers and artist shots for country music stars. “Michael ignited the fire for me,” he says. “Through working with him, I realized I could turn my passion into a career.” But to do so, Doggett needed more training, more exposure. “I knew I needed to go and learn from the best.” The best, unequivocally, being talents like Mark Seliger, Steven Klein, and Annie Leibovitz, all of whom Doggett apprenticed under during his six years in New York as a photography assistant.

Being in the center of the New York photography world was exhilarating and glamorous—at least from a jet-setting perspective. Doggett traveled to shoots in Milan, Paris, Los Angeles, and other hot spots of the fashion world. He worked on set with Madonna, with Obama on the campaign trail, and Desmond Tutu on Richard Branson’s private Necker Island. He had a hand in covers and spreads for Vogue, W magazine, you name it. “My job was to do the technical problem-solving—adjust the lighting or anything else to ensure the photographer’s vision came to life,” says Doggett. The only drawback: it wasn’t his vision.

Even as he was loving being in the fashion and celebrity limelight and soaking up this dynamic language of visual storytelling, Doggett felt a tug, a desire to begin telling his own stories and executing his own vision. He remembered the deep connection he felt to the earth, to indigenous people, and to animals while on a post-graduation family trip to Africa. “I wanted to feel that again,” he says. “I wanted to use photography, and specifically a fashion-inspired lens, to explore a shared sense of humanity with other creatures and cultures.” Deep down, beyond the glitzy fashion camera flash, Doggett knew the answer to the nagging question on a paperweight that had been a graduation gift from his professor of entrepreneurial studies: What would you attempt to do if you knew you could not fail?

“That paperweight still sits on my studio desk,” he says. Above it, taking up an entire wall, is a beguiling black-and-white image of Craig, one of the super tuskers. That image—like the one of a Rendille tribal warrior on the opposite wall, his piercing eyes and chiseled torso as alluring as any GQ cover model, and like all the other prints meticulously rolled up by the studio large-format printers, ready for delivery to his clients and collectors—is Doggett’s answer.

(Left) Tribal Tribute: Doggett lived among the people of the Rendille tribe in Kenya’s Chalbi Desert for a week. Tiye in traditional layers of beaded jewelry that convey information to fellow tribe members. (Right) The Gaze: Mindisayo, a young girl in the Rendille tribe.

You Only Need One

Leaving New York for South Carolina may have been daunting, but Doggett has not looked back. He hasn’t had time to. Since launching his fine art photography practice, Doggett has completed more than 17 series, each telling an extraordinary story of wildlife, ethnography, or haunting landscapes and each involving months, and in some cases years, of in-depth research and preparation, not to mention logistical and travel problem-solving, like how to gain access to Sable Island or the secluded Omo Valley of Ethiopia and live and work off-grid for weeks at a time. Given that level of intensity, Doggett has narrowed his focus to creating only two to three limited-edition series a year, and he alone chooses his subjects and locations; he rarely accepts commissions.

“This allows me to create the level of work I want to do and tell the stories I want to tell,” he says. Through applying his fashion-trained eye and techniques, often using a white backdrop, Doggett distills the subject down to its essential character. “I create a very focused canvas that eliminates distractions and reduces my subjects to their most pure form,” he explains. “To me, fashion uses a visual language that is familiar, people can relate to it, so that’s my preferred aesthetic to draw connections between the viewer and subject.”

Each expedition, each project, is self-funded and often solo—though at times he does bring a colleague and a videographer. He’s produced 12 short films based on the various photo series that have won distinction in the Big Sur International Film Festival and PBS Online Film Festival, in addition to other awards. He’s also published three coffee table books, including the aforementioned Sable horses, as well as Sail: Majesty at Sea and The Slow Road to China. The books, like Doggett’s short films, “expand the narrative” begun by his photography. The up-front investment in time, research, and resources to produce his photo series, books, and films is as immense as the super tuskers—once Doggett covered more than 1,000 miles through India to come away with only one image of a Bengal tiger. “But to me that was a success,” he says. “I’m driven by the prospect of creating something that will stand the test of time, even if it’s only a single image.”

Indeed, the thrill of the chase is part of what drives the artist. On a Rwandan quest to photograph mountain gorillas, he recalls bushwhacking through sweltering jungle. “I was carrying tons of gear through steep vegetation, swarmed by bugs I never knew existed, but that’s what fuels me—not knowing what you’re going to find as you crest the hill. Then coming face-to-face with an animal that resembles a variation of yourself—it took my breath away.”

For his most recent series, “Equus: Underwater Rhythm,” Doggett’s breath was literally taken away. “I had to use scuba gear and become extremely comfortable using an underwater housing for my camera” he says. Going out of his comfort zone to try this new format has delivered. The underwater images, a limited-edition series of 20 photographs, are like a dreamscape, a portal to some mythological realm where mermaid-like horse gods prance with weightless power and grace, an ethereal equestrian water ballet. Here, water serves a similar purpose to a white background for a fashion shoot. “It creates a minimalist environment so you can be completely immersed in the beauty of the horse’s form, with no distractions,” he explains. “This series offers a new perspective on a subject I’ve photographed for decades,” he says of horses, a recurring focus due to the “deep rooted connection that humans have with them.”

(Left) Focal Point: Doggett in his Mount Pleasant studio; about a decade ago, the photographer shifted focus from fashion to documenting indigenous peoples and endangered wildlife. (Right) Next Gen: Moving to the South and starting a family (wife, Kristin; five-year-old daughter, Emerson; and son, Graydon, age four) confirmed Doggett’s commitment and “sense of urgency” to document threatened wild animals and remote places and cultures.

Giving Back

Doggett is a purist. He typically shoots in natural light, using silks and screens to shape the light. He photographs in color then converts the images to black-and-white, dodging and burning to emphasize the elements he wants to bring to the fore. Judging by the many awards and honors he’s earned, including being named the number-one US black-and-white photographer, and fourth globally, by international photo competition One Eyeland in 2020, as well as a distinction from the Royal Photographic Society, Doggett’s eye and techniques are well-honed. Images from his “Omo: Expressions of a People” series are included in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, and his work has been featured in Condé Nast Traveler, Outside, Forbes, Fortune, and Architectural Digest, among others. His collectors include Gloria Steinem, Alec Baldwin, the Waldorf Astoria, and Four Seasons.

One of the keys to Doggett’s success? “Leaving room for spontaneity,” he says—a lesson constantly reinforced as he balances a thriving artistic practice with parenthood. When traveling to Namibia to photograph the immense dunes of Sossusvlei, he had planned to capture long, dramatic shadows but had to shoot at high noon, with no shadows at all. “So I shifted my creative focus and emphasized the macro shapes,” he says.

While flexible and quick to pivot as needed in the field, his mission remains fixed and clear. Doggett’s work is a testimony to wonder and a call to action, a call to respect and care for the exceptional creatures and extraordinary places he photographs if they are to endure. His studio is committed to giving back, through participating in 1% For the Planet and donating a percentage of sales to simpatico nonprofits like the Tsavo Trust and the Jane Goodall Institute, but in a sense, every image is a gift back to the natural world.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, Doggett’s images speak volumes. Look closely, they say. Love what is precious. Protect and revere. “...And nothing else.”

Colossal Shadows: Super Tuskers of East Africa (Captions) from Drew Doggett on Vimeo.